eOrganic author:

Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming

Introduction

The best way to deal with troublemakers at a party is not to invite them in the first place. Similarly, farmers should try to keep the farmgate closed to new, troublesome weed species by not allowing their seeds, roots, rhizomes, or tubers to hitch a ride in manure or other materials brought in from off-farm sources. Weeds are the one thing you do not want to diversify on your farm! The more weed species present, the more likely that one of those weeds will create problems in a particular crop. Many farmers also take precautions to keep localized weed infestations from moving from field to field. However, weed control by sanitation is easier said than done, because weed seeds have so many different ways to sneak into the field:

- Mulch hay can bring large numbers of perennial weed seeds if forage grasses or pasture weeds had formed mature seed when the hay was cut.

- Other mulching materials and organic residues may contain unwanted seed, such as volunteer cereal grains from straw.

- Manure can contain large numbers of weed seeds, many of which pass through the digestive tracts of livestock unharmed. In addition, the readily available nutrients in manure promote rampant growth and prolific seed set in common lambsquarters, pigweeds, and many other agricultural weeds.

- Any compost that has not gone through a “hot” phase sufficient to kill weed seeds (140°F for a week or more) may carry weed seeds.

- Livestock feed grains and crop seeds—especially cereals, cover crops, and forages—may contain weed seeds, depending on their source.

- Soil clinging to tractor tires, planters, and tillage or cultivation implements often contains weed seeds or the roots, rhizomes, or tubers of perennial weeds. While the numbers of seeds thus spread are usually small, rented or shared equipment is notorious for bringing new unwanted species onto the farm.

- Other farm equipment such as mowers and combines can carry weed seeds.

- Weed seeds may be inadvertently brought home from off-farm sites on shoes (in soil) or attached to clothing.

- Newly-purchased farm animals can bring along weed seeds in their fur or their manure.

- Irrigation water can be a major source of weed seeds, especially if it is drawn from a creek or river that receives runoff from weedy fields, pastures, or river banks.

- Roadsides, power line right-of-ways, and railroad beds adjacent to crop fields—so-called “waste areas”—can become sources of weed seeds, especially biennial and perennial species.

- Some weed seeds—especially those in the composite family, such as dandelion and thistle—can blow into fields on the wind.

- Birds and other wildlife can deposit weed seeds in their droppings.

- Floodwaters can bring millions of weed seeds into low-lying or river bottom fields.

How far weed seeds can travel to reach the farm depends on the dispersal process (Fig. 1), as well as the weed species. Knowledge of typical seed dispersal distances through different means can help in fine-tuning sanitation practices.

Figure 1. Agricultural weed seeds can travel over a range of distances, depending on the method of transport. Figure Credit: Fabian Menalled, MSU Extension, Montana State University (adapted from Mohler, 2001).

Because many of these dispersal mechanisms are difficult or impossible to control, sanitation must also include vigilance to detect, isolate, and eliminate new infestations before they spread. Measures to prevent the spread of newly-arrived weeds within or between fields on the same farm can greatly reduce future weed control costs. Watch out for mowing or harvesting operations that can disperse weed seeds throughout a field (see Sidebar). A grain combine header, for example, can effectively capture mature weeds present only at the field edge, thresh the seeds, and disperse them up to the width of the combine towards the field interior. A little manual labor to rogue out problem weeds in field margins before mowing, harvesting, or tilling the field could pay off by preventing them from becoming established in the field’s seed bank.

Sidebar:

A Caution about Combines

The following is excerpted from Davis (2004). NOTE: whereas grain combines are not used in vegetable harvest, some farms may integrate grain and vegetable production in a diversified rotation. Mowing and other field operations can also disperse the seed over a wider area.

"The combine grain harvester is truly a technological triumph, allowing a relatively small number of people to farm large acreages. It is also the most efficient weed seed spreading device ever developed. Before the advent of chemical herbicides, early combine models directed weed seeds separated from grain into a weed seed collection pan for later disposal. As combines and acreages got larger, and herbicides took over as the primary tool for weed control, this feature was eliminated from combines. Weed seeds are now blown out the back of the combine along with the chaff, taking localized weed problems and making them whole-field weed problems. In parts of the world where herbicide resistant weed species have become a major problem, such as Australia and Canada, weed seed collecting combines have reappeared.

"Other farmers, including some in the North Central Region of the U.S., have modified their own equipment to collect weed seeds (note: this is not possible with a rotary combine). One organic farmer in Michigan modified his 1974 Gleaner K series to collect weed seed by taking the weed screen in the reclean elevator and moving it from the bottom to the top of the stack. From there, he routed the weed seed to a 15-gallon drum mounted on the outside of the combine. In 2003, he used the modified combine to prevent seed return from a severe velvetleaf infestation in soybean, and caught over 55 gallons of velvetleaf seed—15 million seeds—on 11 acres."

Sanitation Practices in Organic Weed Control

The following measures can help prevent new unwanted weed species from entering a field’s weed seed bank:

- Minimize the use of off-farm organic inputs that might carry weed seeds, especially hay and other mulch materials. If practical, produce your own mulch by cutting hay or cover crops before they contain mature seeds.

- If you do import mulch hay or other organic materials, try to get relatively seed-free materials. Use hay cut before the forages form seeds, from fields that do not contain serious weeds. Watch out for emergence of weeds likely to arrive with the hay. (NOTE: Also be sure that imported organic materials are free of highly persistent herbicides such as chlopyralid, aminopyralid and picloram, which are sometimes used on lawns or pasture and are highly toxic to vegetables.)

- Compost animal manures and other potentially seedy organic materials at high temperatures to kill weed seeds. Turn and water piles or windrows as needed to ensure that all parts of the mass reach temperatures of 140°F for a week or so. This is essential for manure from off-farm sources, and treating on-farm manure likewise will help keep existing weed species from multiplying or spreading to new fields.

- Learn as much as you can about any “compost,” such as composted manure, municipal leaves, or yard waste, before purchasing. Ask whether it was composted at sufficiently high temperature to eliminate weed seeds. When in doubt, spread a representative sample 1–2 inches deep in a seed flat, keep moist and in a warm place that receives daylight for a couple of weeks, and see what emerges. (NOTE: if you are using urban yard waste or compost that contains grass clippings, check for herbicide residues by filling a seed flat with the compost and sowing some lettuce, tomato, or squash seeds in the flat. These vegetables are highly sensitive indicator plants for herbicide residues.)

- Obtain vegetable and other crop seeds, as well as livestock/poultry feed, from reliable sources that can verify them as free of weed seeds. A label showing a minimal weed seed content (e.g., 0.01%) may be acceptable if it is also certified as free of “noxious weeds.” When in doubt, examine the crop seed carefully. If possible, sieve to separate the desired crop seed from foreign material and check the latter for seeds or plant it in a flat to see if any problem weeds emerge.

- If possible, avoid purchasing seeds, feed, and other inputs from distant geographic regions or oveseas, as these are are more likely to introduce potentially invasive exotic species.

- Clean tractor tires, four-wheelers, wagons, trailers, and tillage/cultivation equipment between operations on different fields. Use a power washer or a well-pressurized hose to remove soil clinging to tire treads, plowshares, tiller tines, planter shoes, and other tools before entering the next field. Blow or vacuum out harvesters, combines, and mowers. Be especially vigilant about rented or shared equipment that has recently been used on other farms. Ideally, clean it thoroughly before bringing it onto the farm, and then clean it again when you are finished for the benefit of the next user.

- Watch for perennial roots, rhizomes, and tubers caught in tiller tines and other tools; embedded in crowns or roots of purchased vegetable starts or nursery stock; or in pots.

- Avoid becoming a weed seed vector. After visiting a weedy field or field margin (on your own farm or elsewhere) remove soil from shoes/boots, and check clothes for adhering weed seed before entering another field or garden.

- Utilize weed-seed-free irrigation water if practical; otherwise install and maintain filters to remove weed seeds from irrigation water.

- Keep new livestock in quarantine for a suitable period of time before turning them out into fields or pastures. Make sure the quarantine area is one in which new weeds can be readily detected and eliminated.

- Manage field margins, powerline rights-of-way, roadsides, ditches, waterways, and railroad beds on or adjacent to the farm to minimize growth and seed set by agricultural weeds. Mow before weeds begin to set seeds. Plant these areas with desirable vegetation to stabilize soil and provide habitat for weed seed predators and other beneficial organisms. Use native perennial plantings, such as prairie seed mixtures, to prevent the buildup of agricultural weeds in areas bordering fields (Davis, 2004).

Excluding New Weeds: What is Practical?

Whereas the goal of sanitation is to prevent the establishment of new, damaging weeds on the farm, it may not be possible to avoid totally the introduction of any and all new volunteer plant species. The farmer must replace nutrients sold off the farm in produce in order to maintain soil health and fertility. Organic growers utilize organic sources such as manure, mulch hay, and cover crops to replenish nutrients and organic matter. Commonly, vegetable growers obtain some of these inputs from off-farm sources to balance the export of nutrients when crops are marketed. Purchased livestock feeds, cover crop seeds, and even vegetable seeds may contain some weed seeds.

Efforts to eradicate every newcomer may not be necessary or practical. For example, appearance of a small, low-growing weed like buckhorn plantain or carpetweed may not pose enough of a threat to vegetable production to merit investing labor and resources in an eradication effort. The most practical approach might be to learn what weed species would likely cause serious damage if they arrived on the farm. These might include weed species recognized in the farm’s region as major problems in vegetable production or listed as invasive exotic plants. Farmers can post a “most wanted” notice with a photo and brief description of a few of the region’s worst agricultural weeds to watch out for, so that all who work on the farm can help detect new infestations early enough to facilitate their eradication (see Sidebar).

Most (Un)Wanted Weeds: Examples from Across the Nation

The Northeast: Hairy Galinsoga

Figure 2. Hairy galinsoga, Galinsoga ciliata. Figure Credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Hairy galinsoga (Galinsoga ciliata, Fig. 2) and the closely related smallflower galinsoga (Galinsoga parviflora) are extremely prolific and are considered some of the most difficult-to-control weeds of vegetable production in the northeastern United States. A small, much-branched summer annual 5–25 inches tall, galinsoga has oval to triangular leaves with three prominent veins and slightly toothed margins arranged oppositely (in pairs) on the stem. Within 30 days after emergence, galinsoga bears tiny yellow composite blooms that rapidly form small seeds, each with a white tuft of hairs. Hairy galinsoga is densely covered with hairs on stems, petioles, and upper leaf surfaces; smallflower galinsoga has few or no hairs.

Emerging seedlings are initially vulnerable to cultivation, but plants rapidly develop a tenacious, fibrous root system and can reroot after cultivation if the soil is moist. Plants set thousands of mature seeds within 35–40 days after emergence. The nondormant seeds can germinate immediately after being shed, thus creating two or three generations within the frost-free growing season.

This weed spells trouble for vegetable production mainly because of its ability to multiply prolifically. Production of up to 4 billion galinsoga seeds (weighing about 1,600 lb) per acre has been observed. Crops direct-sown in soil with a high galinsoga seed bank will be choked out by this weed unless repeated, intensive cultivation and hand weeding are done.

If galinsoga is not already established on the farm, early detection and eradication of any new galinsoga infestation will pay off in tremendous labor savings. Fortunately, populations of galinsoga seed can be markedly reduced by one pass with a moldboard plow to bury the short-lived seeds deep in the soil profile, followed by avoidance of additional deep tillage for three years to avoid bringing any viable seeds back to the surface. Rotating infested fields to sod (pasture or hay) for a few years can also eliminate galinsoga.

The Deep South, Southern California, and Southwestern US: Purple Nutsedge

Figure 3. Purple nutsedge, Cyperus rotundus. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

This diminutive plant (4–24 inches) is native to tropical regions where it causes tremendous damage to such a wide range of food, fodder, and fiber crops that it is considered the world’s worst weed (Holm et al., 1991). It has the three-ranked leaf arrangement and stems triangular in cross section characteristic of sedges. Distinguish purple nutsedge (Cyperus rotundus) from its close relative yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus) by its slightly darker green leaves, purplish (rather than golden) flower heads, and tubers arranged in strings along the rhizome (yellow nutsedge forms tubers only at tips of rhizomes). Yellow nutsedge is a serious weed in its own right, especially in the Northeastern and Pacific Northwest regions.

Purple nutsedge is an invasive perennial weed propagated by rhizomes and tubers (Fig. 3). It is strongly allelopathic (growth-inhibiting) to a wide spectrum of crops and other plants. In a heavy infestation, the dry weight per acre of tubers in the soil can exceed the total (above- and belowground) dry weight of a mature crop of corn or sorghum (Holm et al., 1991). Each tuber can produce a new plant whenever conditions are favorable.

Purple nutsedge is incredibly heat tolerant (to 140°F), quite drought tolerant, and fairly tolerant to brief flooding. Its one weakness is its sensitivity to cold, which restricts its range within the US to the warmer parts of the South and Southwest. Near the northern edge of its range, purple nutsedge is not considered highly competitive, probably because of suboptimal temperatures. However, shifts in hardiness zones related to global climate changes may allow this weed to spread northward or to become more aggressive within its current range. Thus, any vegetable grower in the South should be on the lookout for any first appearance of purple nutsedge on the farm, and take prompt measures to eradicate it.

The Midwest: and Pacific Northwest: Common Purslane

Figure 4. Common purslane (Portulaca oleracea). Figure Credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Common purslane (Portulaca oleracea, Fig. 4) is an extremely drought-tolerant summer annual weed that is difficult to control by cultivation. It forms a prostrate mat of succulent, fleshy leaves arranged oppositely (in pairs) on succulent stems. Leaves are obovate (rounded and widest toward tip), green on the upper surface, and tinged with maroon on the lower surface. The small (1/3 inch), yellow five-petaled flowers open only in sunny weather.

Fragments of the purslane plant reroot easily to give rise to new plants, and larger uprooted plants can mature seed even without re-establishing root systems in the soil. The plant is self-pollinated, and flowers can be fertilized even before they open. Seeds are tiny and long-lived. All of these traits make it difficult to keep purslane from propagating itself in cultivated fields and gardens.

Purslane tends to come up in the hottest part of summer, though it can emerge and grow anytime during the frost-free growing season. It grows most vigorously on warm, fertile soils where it can compete severely with newly emerging crops. Although low-growing and not likely to affect established, tall crops like corn or pole beans, common purslane can seriously interfere with lower-growing vegetables like lettuce, salad greens, carrots, and onions, and may necessitate hours of tedious hand weeding.

Common purslane is widespread around the world, and considered the world’s 9th most costly agricultural weed. If it has not yet arrived at your farm, efforts at early detection and eradication can pay off. Cultivate out emerging weeds when they are still tiny. After that, exploit this weed’s one weakness—intolerance to shady, damp conditions—>by using organic mulch, planting fast-growing cover or vegetable crops that form a dense canopy, or both.

The Mid-Atlantic, Midwest, and West: Canada Thistle

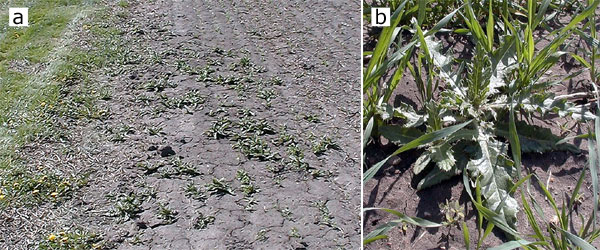

Figure 5. Canada thistle, Cirsium arvense. (a) vegetative spread into a cultivated plot from a grassy border. (b) young vegetative shoot sprouting from rhizome among small grain plants in spring. Figure credits: Ed Zaborski, University of Illinois.

Canada thistle (Cirsium arvense, Fig. 5) is a major weed of pastures and small grains. It can also become quite troublesome in vegetable crops, especially where tillage has been reduced in efforts to improve soil quality or manage annual weeds, or where hay mulch containing mature thistle seeds has been used. An invasive or wandering perennial, Canada thistle propagates through an extensive, deep, rapidly spreading network of roots and rhizomes giving rise to new shoots. Seedlings and shoots from rhizomes initially form low rosettes of lobed, spiny leaves. Later, stems elongate to several feet in height, bearing clusters of small (1-inch) pink to purple flower heads.

Because of its deep and spreading root/rhizome system, Canada thistle is quite drought tolerant, competitive against crops, and difficult to control with tillage and cultivation. In addition, it suppresses the growth of many crops through allelopathy (release of natural herbicidal or growth-inhibiting compounds). The weed can be gradually weakened and eliminated over a couple years’ time by chopping out all shoot growth in late spring (when root reserves are at a minimum) and repeatedly removing any additional emerging growth when shoots reach the 3–4 leaf stage.

Vegetable growers anywhere should consider this a “most wanted weed” since early detection of a localized infestation makes the work of eradication feasible. When Canada thistle has become established in a field, two or three years of alfalfa, cut for hay or chopped as green manure, have been shown to be effective in significantly reducing the thistle population.

Across the United States: Bindweeds

Hedge bindweed (Calystegia sepium) is a rhizomatous, vining, perennial weed with triangular or arrowhead-shaped leaves 2–4 inches long, and solitary, white, bell-shaped flowers about 2 inches long. This bindweed emerges in late spring from rhizomes or rhizome fragments in the soil, and will twine around and climb any plant, fence, or other support it encounters (Fig. 6a). In addition to reproducing by seed, bindweed spreads rapidly through an extensive underground network of roots and fleshy white rhizomes throughout the top 12–24 inches of soil (Fig. 6b). The small rhizome fragment shown separate from the main plant in Fig. 6b is large enough to send up a vigorous new shoot.

Figure 6. Hedge bindweed (Calystegia sepium), showing (a) habit of growth and (b) root/rhizome system. The small rhizome fragment (lower left) can propagate the weed, even if buried at a depth of 6 inches. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Hedge bindweed is notoriously difficult to control, because its succulent, yet brittle, rhizomes are readily fragmented by tillage, cultivation, or attempts to pull or dig them out manually. Fragments as small as 0.3 inch long can regenerate new plants from a depth of a couple inches, and larger pieces can send up shoots from a depth of a foot or more. The weed is moderately tolerant to both drought and excessive moisture, and has an amazing ability to survive and grow for long periods of time without light. Mulching is useless against hedge bindweed, which has been known to penetrate three-foot high piles of compost or mulching materials, forming vigorous vines upon emergence.

Field bindweed (Convovulus arvensis) is a closely related rhizomatous perennial vine with somewhat smaller leaves and flowers compared to hedge bindweed. Leaf shape is rounded at the tip with a pair of lobes near the base pointing away from the stem. Flowers are small (0.5–1 inch long), funnel shaped, white to light pink, and borne singly or in small clusters of 2–5. Field bindweed has an extensive and incredibly deep root system, extending 15–20 feet below the surface. As a result, field bindweed is extremely drought tolerant and quite difficult to eliminate by tillage alone. However, it is not as shade tolerant as hedge bindweed, and thus can be suppressed to some degree by crops that form a very dense canopy, such as pumpkin or winter squash, or by smother crops of buckwheat.

In addition to competing for light, water, and nutrients, both bindweeds interfere with leaf opening and plant growth through their twining habit of growth, and can even smother crops outright. They can also overcome competitive cover crops like winter rye by simply climbing their stems. Field bindweed is a particularly serious problem in the Pacific Northwest in perennial crops and winter cereal grains.

If bindweeds are not already established on the farm, don't let them get a foothold! Digging out ALL of a localized infestation may seem like a lot of work, but it will save bigger headaches down the road. Repeatedly removing top growth—every three weeks during the growing season for up to two years—and, if practical, rhizomes within the top few inches of soil, will gradually weaken bindweeds, and a combination of tillage and fast-growing cover crops can also be effective.

Hay mulch is a particularly popular material for organic vegetable growers, and with good reason. A three or four inch layer of loose hay keeps the soil cool and moist during hot summer weather, hinders many annual broadleaf weeds, keeps fruiting vegetables cleaner, prevents soil crusting by hot sun and heavy rain, adds organic matter, and may provide slow-release nutrients. However, it can be difficult indeed to obtain hay that is completely free of seeds of the forage species themselves or other weeds. Often, the best one can do is find hay that does not carry large numbers of seeds. Some growers let bales of potentially seedy hay stand outdoors in the weather for one year to encourage weed seed decay before spreading as mulch. This substantially reduces, but does not eliminate, the seed burden. In addition, the rotted hay can be unpleasant and hazardous to spread because of mold spores.

This article is part of a series on Twelve Steps Toward Ecological Weed Management in Organic Vegetables. For more on managing the weed seed bank, see:

References and Citations

- Davis, A. S. 2004. Managing weed seedbanks throughout the growing season [Online]. New Agriculture Network Vol. 1 No. 2.

- Grubinger, V. 2004. Farmers and their innovative cover cropping techniques [VHS tape/DVD]. University of Vermont Extension, Burlington, VT.

- Holm, L. G., D. L. Plucknett, J. V. Pancho, and J. P. Herberger. 1991. The world’s worst weeds. Kriegar Publishing Company, Malabar, FL.

- Menalled, F. 2008. Weed seedbank dynamics and integrated management of agricultural weeds. Montana State University Extension MontGuide MT200808AG. (Available online at: http://www.msuextension.org/publications/AgandNaturalResources/MT200808AG.pdf) (verified 11 March 2010).