eOrganic author:

Dr. Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming

Abstract

In organic production, tomato, pepper, and eggplant are normally started indoors and transplanted to the field to give them a head start on the weeds. Crops kept free of weeds for the first 4–8 weeks (tomato) or 8–10 weeks (eggplant, pepper) after transplanting can usually outcompete later-emerging weeds. However, late-season weeds can interfere with harvest, promote disease, and propagate themselves.

The most serious weeds of solanaceous (nightshade family) vegetables in the southern United States include yellow and purple nutsedges, morning glories, pigweeds, solanaceous weeds that host tomato or pepper diseases, and several winter annual weeds that harbor tomato spotted wilt virus and an insect pest (thrips) that transmits the virus from weed to crop. Fields heavily infested with these weeds should not be planted in tomato, pepper, or eggplant, and should be rotated to weed-smothering cover crops or perennial sod until weed populations decline to tolerable levels.

Important weed-preventive measures include: crop rotations that alternate warm- and cool-season vegetables, cover cropping, providing sufficient but not excessive nutrients from slow-release organic sources, and stale seedbed (planting delayed after seedbed preparation to allow removal of the inital flush of weeds) to draw down the weed seed bank.

Most organic farmers use one of two strategies to control weeds in solanaceous vegetables:

- Black plastic mulch laid just before transplanting; alley weeds managed by cultivation, mowing, or organic mulch.

- Cultivation to remove early-season flushes of weeds, followed by hay, straw, or other organic mulch.

Variations on these strategies include opaque white or light-reflecting (aluminized) plastic mulch for later plantings when soil warming is not desired; spreading organic mulch over plastic films several weeks after planting to prevent excessive soil heating; and in situ organic mulch from mowed or roll-crimped cover crops.

This article outlines organic weed management strategies and techniques for tomato and related vegetable crops, based on an understanding of:

- General principles of ecological weed management.

- Crop growth habits, life cycles, cultural practices, and organic production systems.

- Inherent vulnerabilities and strengths of tomato, pepper, and eggplant in relation to weeds.

Introduction

Tomato, pepper, and eggplant require good early-season weed control for successful production. Once established, these warm-season solanaceous vegetables become less vulnerable to competition from newly-emerging weeds, and tall tomato varieties can hinder weed growth by shading. late-season weeds must be managed to maintain adequate air circulation around crop foliage, and to prevent weed propagation during the long harvest season.

Crop Life Cycle and Growth Habit, Impacts of Weeds, and Minimum Weed-Free Period

Tomato, pepper, and eggplant are frost-tender summer annual crops in the solanaceous (nightshade) plant family. They require warm temperatures and an adequate supply of nutrients throughout the season to support good growth and yields. Newly-emerged seedlings are highly vulnerable to weed competition, and are usually started indoors in a weed-free potting mix. Once established, these crops become more tolerant of weed pressure. In tomato, the minimum weed-free period (to prevent yield losses to weed competition) has been estimated as the first 4–8 weeks after transplanting (Monks, 1993; Riggs et al., 1991; Teasdale and Colacicco, 1985; Weaver and Tan, 1983). Minimum weed-free periods for pepper and eggplant may be a little longer (8–10 weeks), owing to their slower development and shorter stature.

Because harvests continue until plants are killed by fall frost or disease, mature solanaceous crops remain in the field for a long period, during which additional weed management may be needed. Weeds that emerge after the crop's minimum weed-free period and are allowed to grow can interfere with harvest, promote disease by harboring pathogens or curtailing air circulation, or set seed.

When solanaceous vegetables reach a height of 12 inches or so, they tolerate some hilling up during cultivation, which buries and kills small within-row weeds. Hilling can benefit tomato by stimulating adventitious rooting from the stem, and diverting excess moisture away from the base of the plants (Diver et al., 2007). However, hilling can promote development of southern stem blight (Sclerotium rolfsii), and should be avoided where this pathogen is present (Louws, 2009).

Sweet and hot peppers, eggplant, and compact determinate varieties of tomato (varieties that grow to a fixed mature size and ripen all their fruit in a short period) form upright, bushy plants two to three feet tall. Indeterminate and semi-determinate tomato varieties form longer vines (five feet or more), and are normally staked or trellised.

Tomato prefers moderately warm conditions, giving best growth and production at daily mean air temperatures of 70–75 °F (Peet, 1996, Swaider et. al, 1992) and soil temperatures of 68–86 °F (Tindall et al., 1990). On good soil without hardpan (compact layer that restricts root growth), tomato forms a deep (five feet) root system, which can make established plants less susceptible to weed competition for soil moisture. The heavy foliage of a vigorous tomato crop can shade out weeds; however managing the crop to promote canopy closure can aggravate disease problems, leading to defoliation and yield losses.

Peppers require similar growing conditions to tomatoes, and prefer slightly warmer temperatures, especially the pungent varieties (Peet, 1996, Swaider et al., 1992). Unlike tomato, pepper has a shallow root system, which makes it more vulnerable to weed competition for soil moisture, and to detrimental root pruning from cultivation. Pepper is less prone to foliar diseases than tomato, and can be managed for canopy closure within the bed when disease pressure is light.

Eggplants prefer higher temperatures (daily means about 80 °F, nights not cooler than 65 °F) and a longer growing season than other solanaceous vegetables (Swaider et al., 1992). Like pepper, it can be managed to close canopy within the bed for suppression of late-emerging weeds. The crop develops a moderately deep root system (four feet), and can tolerate shallow cultivation for weed control.

Cultural Practices and Weed Management

Tomato, pepper, and eggplant are normally started in the greenhouse in a weed-free potting mix, and transplanted to the field at an age of 5–7 weeks (tomato) or 8–10 weeks (pepper, eggplant). Although some large scale conventional growers direct-seed solanaceous crops and apply selective herbicides, nearly all organic farmers minimize early-season weed competition by transplanting vigorous starts (Fig. 1). Tomato is set out after the last spring frost date; pepper and eggplant are often planted a few weeks later, when the soil is thoroughly warm.

Some farmers do succession plantings, with early crops set out in high tunnels before the last spring frost date, and field plantings continuing into late June or early July. Later plantings set out after the late spring flush of weed emergence allow the farmer to reduce weed pressure by preparing a stale seedbed or growing a weed-suppressive spring cover crop. When using the stale seedbed technique (also known as false seedbed), the farmer delays crop planting for several weeks after initial seedbed preparation to allow one or more flushes of weed seedlings to emerge. These are removed by shallow cultivation or flame weeding, and the crop is planted immediately after the final cultivation or flaming.

Figure 1. (a) Vigorous tomato starts at 6 weeks after seeding, ready for transplanting. (b) Pepper starts 8 weeks after seeding. Photo credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Tomato, pepper, and eggplant require a moderate amount of available N, about 70–130 lb/ac from planting through early fruit set, and ample phosphorus (P) and potassium (K) to support good root growth and fruit quality, respectively (Swaider et al., 1992). Good organic soil management and attention to maintaining optimum growing conditions can enhance the crop's competitiveness toward weeds. Planting when temperatures are below optimum can prolong the minimum weed-free period. Providing too much available N early in the season can give weeds a competitive advantage over the crop, and excessive N later in the season may result in plants with dense foliage and few fruit.

Tomato is usually planted in single rows spaced 5–6 feet apart, either in raised beds or on the flat, with individual plants set 12–48 inches apart, depending on cultivar and production system. Some organic growers use wider row spacing (8–10 feet) to enhance air circulation, sometimes planting a low-growing vegetable or cover crop in the intervening spaces. Plants are normally supported (staked, trellised, or caged), and pruned (suckered) regularly to promote rapid drying of foliage for disease control, and to enhance fruit yield, quality, and ripening. Trellising and stake-and-weave systems that train the crop to a single line allow close cultivation or mulching under the plants, while cages limit weed control options near plant bases. Short varieties and processing tomatoes are sometimes grown without support (ground culture); however, the sprawling plants are difficult to keep weeded unless a plastic mulch is used.

Pepper and eggplant are often planted in staggered double rows, with plants spaced 18–24 inches apart in the row, and double rows on 5–7 foot centers. With this planting pattern, the crop often closes canopy within the bed, thereby suppressing the growth of late-emerging weeds. Pepper is sometimes staked to prevent the shallow-rooted plants from falling over during heavy fruit set.

Solanaceous crops respond very well to mulching. Many commercial organic producers routinely use synthetic mulch—most often black polyethylene film (black plastic)—for tomato, pepper, and eggplant (Fig. 2). Black plastic effectively controls most weeds and warms the soil, thereby promoting crop earliness and sometimes total yield. Drip irrigation is usually laid under the mulch to deliver water and liquid organic fertilizer to the crop. Some growers prefer black woven landscape fabric, which can be reused for seven or more years. Weeds emerging through planting holes are removed manually, and alley weeds are managed by hoeing, cultivation, mowing, organic mulch, or cover cropping.

NOTE: When plastic or other synthetic mulches are used for organic production, they must be removed from the field at the end of the growing or harvest season.

Figure 2. (a) Vegetable growers setting tomato starts into black plastic mulch. (b) Tomato at flowering in black plastic, with hay mulch in alleys. Photo credits: (a) Becky Crouse, Marketing Manager, Potomac Vegetable Farms, Purcellville, VA; (b) Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Because tomato yield and quality can suffer from excessive soil heating, some growers spread straw or hay over black plastic mulch when summer heat arrives, or use a light-colored plastic for later plantings. In hot climates, a light-reflecting film mulch may be appropriate for main-season or late plantings of pepper and eggplant as well (Fig. 3).

Figure 3. This light-reflecting film mulch (opaque polyethylene with an aluminized surface), results in lower soil temperatures than black plastic, and repels aphids and some other pests from the pepper crop. Photo credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

If plastic mulch is not used, farmers either hoe or cultivate the crop as needed through the minimum weed-free period, or cultivate once or twice, then spread an organic mulch, such as straw or hay, to delay weed emergence until the crop is fully established (Fig. 4). Because organic mulch conserves moisture and moderates soil temperature, it can enhance tomato yields if applied after the soil has warmed sufficiently (Schonbeck and Evanylo, 1998).

Figure 4. (a) Tomato in hay mulch passed through its minimum weed-free period before weeds began to break through the mulch. (b) Straw mulch, applied after cultivation and when soil temperatures were near optimal for eggplant and pepper, has given excellent weed control. Crops were planted in double rows, and the eggplant has closed canopy, thus shading out late-emerging weeds. Photo credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Tall tomato varieties grown on trellises or tall stakes can cast sufficient shade to hinder between-row weed growth. However, in moist conditions, the tomato crop may lose its foliage to diseases toward the end of the harvest period, which allows weed growth to resume.

Most Serious Weeds in Solanaceous Crops in the Southern Region

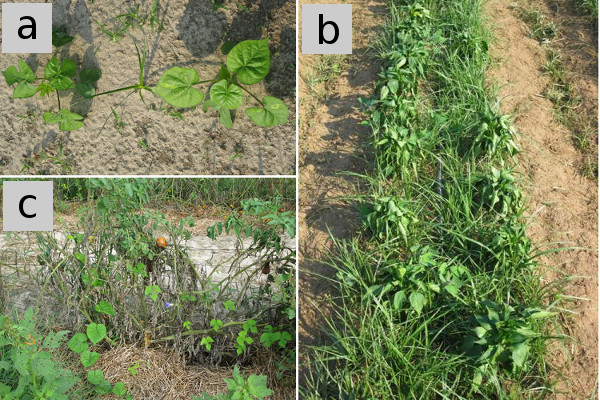

Some of the most widespread and troublesome weeds in solanaceous crops in the Southern region include yellow nutsedge (Cyperus esculentus), purple nutsedge (C. rotundus), morning glories (Ipomoea spp.), and pigweeds (Amaranthus spp.) (Fig. 5) (Webster, 2006). Bermuda grass (Cynodon dactylon), johnsongrass (Sorghum halapense), crabgrasses (Digitaria spp.), foxtails (Setaria spp.), and galinsoga (Galinsoga spp.) have also been cited as major weeds of tomato family in some southern states.

Figure 5. Some troublesome weeds for solanaceous crops: (a) Yellow nutsedge and two species of morning glory emerging in alley between tomato rows. (b) Purple nutsedge competing severely against pepper. (c) late-season morning glories climbing mature tomato plants, with pigweeds growing in alleys (foreground). Photo credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Morning glories are especially troublesome because they can emerge through six inches of straw mulch, readily grow toward and emerge through planting holes in plastic mulches, and climb crop plants. The fast-growing, entangling vines interfere with harvest and can smother the crop.

The sharp-pointed shoots of emerging nutsedges and Bermuda grass can penetrate black plastic film or landscape fabric. The weeds then compete with the crop, and complicate end-of-season mulch removal.

Pigweeds compete aggressively against solanaceous crops, owing to their tall stature and rapid growth during hot weather. Later-emerging pigweed can cause problems, even when the crop is large enough to shade out most grassy weeds and nutsedges.

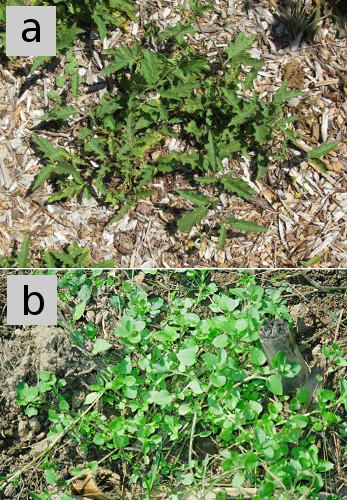

Horsenettle (Solanum carolinense) (Fig. 6a), black nightshade (Solanum nigrum) and other solanaceous weeds are alternate hosts for diseases such as early blight (Alternaria solani), septoria leaf spot (Septoria lycopersici), and late blight (Phytophthora infestans) of tomato, and phytophthora blight (P. capsici) of pepper. Many weed species, including winter annuals like common chickweed (Stellaria media) (Fig. 6b), mouse ear chickweed (Cerastium vulgatum), cutleaf evening primrose (Oenothera laciniata), and cudweeds (Gnaphalium spp.) can harbor tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) and thrips (Thysanoptera), an insect pest that acts as a vector (carrier) and transmits the virus from weed to crop (Louws, 2009; Martinez, 2008). TSWV is most serious in areas with mild winters that do not kill off thrips populations.

Figure 6. Two weeds that pose a disease and pest hazard to solanaceous crops. (a) Horsenettle hosts early blight and septoria leaf spot of tomato, phytophthora blight of pepper, and false potato beetle, which can severely damage eggplant. (b) Common chickweed can harbor the tomato spotted wilt virus (TSWV) and its thrips vector over the winter, thereby propagating the disease from one season to the next. Photo credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Preventive Weed Management in Solanaceous Crops

Preventive weed management begins with planning and field preparation. If possible, avoid planting tomato, pepper, and eggplant in fields with high populations of nutsedge, Bermuda grass, or other aggressive weeds. Use stale seedbed prior to planting to reduce seed populations of pigweed, morning glory, and other summer annual weeds. Weeds known to carry a disease or pest of solanaceous crops that is prevalent in the area should be well controlled before rotating the field to tomato or other crops in this plant family.

A good crop rotation that includes weed-smothering cover crops can reduce weed problems in tomato, pepper, and eggplant (Diver et al., 2007). Alternate warm- and cool-season vegetables in successive years, and grow competitive summer cover crops like buckwheat, cowpea, and sorghum–sudangrass during the season prior to tomato family production. Rotate heavily weed-infested fields into a perennial grass–clover sod for 1–3 years to reduce the weed seed bank.

Optimize soil temperature for crop establishment. For early plantings, use black plastic or fabric mulches, low or high tunnels (Fig. 7), or other strategies to raise soil temperature, so that crop development is not delayed by cold soil. Be sure the soil is thoroughly warm, (~70 °F) before transplanting eggplant or hot pepper. Delay application of straw or other soil-cooling mulches near plants until the soil has reached optimal temperatures. For late-season tomato plantings during hot weather, use a white or reflective film mulch (for best weed control, use an opaque white-on-black film, or coat black plastic with a nontoxic whitewash), or apply straw soon after planting to limit solar heating of the soil.

Figure 7. Tomato planted in March in a high tunnel will begin producing fruit by June at Dayspring Farm in the Tidewater region of Virginia. The companion crops of lettuce and bok choi have limited early-season weed growth, and will soon be harvested. Photo credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Use slow-release organic nutrient sources to meet crop nutritional needs. Avoid more soluble, faster-releasing fertilizers, which could stimulate early-season growth of pigweeds, black nightshade, and other N-responsive weeds. On good, biologically active soil, tomato N needs can be fully met with legume cover crops and compost, and yield better with these N sources than with soluble fertilizers (Diver et al., 2007).

Use in-row drip irrigation to deliver water and liquid organic fertilizers (if needed) preferentially to the crop (Fig. 8). Subsurface drip irrigation (lines buried several inches deep in the crop row) provides moisture to crop roots while leaving the soil surface dry and thereby deterring weed seed germination.

Figure 8. In-row drip irrigation can give the crop the edge over weeds, especially in a dry season. A mulch application would further enhance the crop's advantage. Photo credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Transplant the crop immediately after preparing the bed, especially if plastic mulch is not laid before planting. Even a couple days' delay can give the weeds a significant head start. For tomato, choose row spacing, plant spacing, and method of support that optimizes air circulation for disease control, and facilitates cultivation or mulching. For pepper and eggplant, where disease pressure is light, plant a staggered double row at a plant spacing that promotes canopy closure within the bed or grow zone without unduly crowding the plants.

Cultivation and Other Weed Control Tactics

If plastic film or fabric mulch is not used, cultivate or hoe around the plants when the first flush of weeds is less than one inch tall. Cultivate shallowly to avoid root pruning, especially in pepper. If crop plants are large enough and the southern stem blight pathogen is not present in the soil, adjust cultivation implements to throw soil into the crop rows to bury small within-row weeds, rather than trying to sever or uproot them.

Without mulch, as many as three cultivations may be needed before the end of the minimum weed-free period. Many organic growers hoe or cultivate once or twice to remove early weeds, then apply 3–4 inches of straw, hay, or other organic mulch. This approach conserves soil moisture, adds organic matter, prevents soil splash during rains, and can provide excellent weed control in fields that are not heavily infested with aggressive perennial weeds or morning glories.

For tomato, pepper, and eggplant transplanted into plastic film or fabric mulch, some manual labor is usually needed to remove weeds that emerge through planting holes. Usually, one manual weeding is sufficient, after which the growing crop shades out emerging weeds. Control alley weeds by cultivation, hoeing, mowing, or spreading straw or other organic mulch in alleys and overlapping edges of the plastic.

Once the crop has passed through its minimum weed-free period, manage later-season weeds so that they do not hinder air circulation and promote foliar diseases (Fig. 9), interfere with harvest, or propagate themselves. Pull or cut morning glories and other vining weeds before they begin to climb the crop. Remove large "escapes" before they set seed. Hoe, cultivate or mow closely any nutsedge or other invasive perennials to disrupt formation of new rhizomes and tubers.

Figure 9. These weeds emerged late enough not to compete directly with the established tomato crop; however, they reduced air circulation and promoted the development of fungal diseases, which have defoliated the lower parts of these plants. Photo credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Additional Weed Management Strategies

Winter cover crops, such as cereal rye–hairy vetch or barley–crimson clover, can be roll-crimped or flail-mowed for no-till planting of summer vegetables. The rye–vetch mulch appears especially promising for tomato production. In a study in Beltsville, MD, tomato planted in mow-killed hairy vetch yielded about 20% more than tomato in black plastic (Abdul-Baki and Teasdale, 1993, 1997). Mowed rye mulch can suppress weeds for 4–8 weeks without adversely affecting tomato yield (Smeda and Weller, 1996) and vetch residues have been shown to enhance disease resistance, prolong active photosynthesis and delay leaf senescence in tomato by modifying tomato gene expression (Kumar et al., 2004). No-till planting into mechanically killed cover crop is recommended for main-season and late tomato plantings, but not early plantings, as the cover crop mulch may delay soil warming, crop establishment, and fruit ripening.

Winter cover crops can be strip-tilled several weeks before tomato or pepper planting to promote soil warming in the crop grow-zone. Cover crops growing in alleys can be maintained by mowing to keep alley weeds down (Fig. 10); in some cases, the mowings can provide clean mulch for the vegetable. Season-long living mulches of white clover, subterranean clover, or ryegrass, managed by mowing or partial tillage, have also been used successfully for alley weed control in tomato (Diver et al., 2007). However, clovers host nematode pests that affect tomato, such as root-knot nematode; thus, clovers should not be grown with or immediately before solanaceous vegetables in fields in which these nematode pests are present.

Figure 10. A winter rye cover crop was strip-tilled prior to transplanting tomato at Seven Springs Farm in Check, VA (Appalachian region). The cover crop, maintained by mowing, has suppressed alley weeds. Photo credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Finally, cover crops can be planted in alleys between beds several weeks after vegetable planting (relay intercropping) to suppress weeds, protect soil, and add organic matter. Examples include buckwheat, cowpea, millet, or white clover, mowed if needed to maintain air circulation around the crop.

References Cited

- Abdul-Baki, A. A., and J. R. Teasdale. 1993. A no-tillage tomato production system using hairy vetch and subterranean clover mulches. HortScience 28: 106–108.

- Abdul-Baki, A. A., and J. Teasdale. 2007. Sustainable production of fresh market tomatoes and other summer vegetables with organic mulches. Farmers' Bulletin No. 2279. USDA–Agriculture Research Service, Washington, D.C. (Available online at: https://www.ars.usda.gov/ARSUserFiles/oc/np/SustainableTomatoes2007/TomatoPub.pdf) (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Diver, S., G. Kuepper, and H. Born. 2007. Organic tomato production [Online]. Available at: (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Kumar, V., D. J. Mills, J. D. Anderson, and A. K. Mattoo. 2004. An alternative agriculture system is defined by a distinct expression profile of select gene transcripts and proteins. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 101: 10535–10540. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1073/pnas.0403496101) (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Louws, F. 2009. Managing vegetable diseases. Presentation at the 24th annual Sustainable Agriculture Conference of the Carolina Farm Stewardship Association, Black Mountain, NC, Dec 5, 2009.

- Martinez, N. 2008. Tospoviruses in Solanaceae and other crops in the coastal plain of Georgia: Epidemiology, weed hosts. University of Georgia. (Available online at: https://studylib.net/doc/12948448/tospoviruses-in-solanaceae-and-other-crops-in-the-coastal...) (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Monks, D. 1993. Veg-I-News. Cooperative Extension Service, North Carolina State University. Vol. 12, No. 4.

- Peet, M. 1996. Sustainable practices for vegetable production in the South. Focus Publishing, R. Pullins Company, Newburyport, MA.

- Riggs, D.I.M., R. R. Bellinder, and R. W. Wallace. 1991. The effect of one, two and three month weed-free periods on yield of late season tomatoes. HortScience 26: 152.

- Schonbeck, M. W., and G. E. Evalylo. 1998. Effects of mulches on soil properties and tomato production. I. Soil temperature, soil moisture, and marketable yield. Journal of Sustainable Agriculture 13: 55–81. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1300/J064v13n01_06) (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Smeda, R. J., and S. C. Weller. 1996. Potential of rye (Secale cereale) for weed management in transplant tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum). Weed Science 44: 596–602. (Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4045642) (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Swaider, J. M, G. W. Ware, and J. P. McCollum. 1992. Producing vegetable crops, 4th ed. Interstate Publishers, Inc, Danville, IL.

- Teasdale, J. R., and D. Colaccicco. 1985. Weed control systems for fresh market tomato production on small farms. Journal of the American Society of Horticultural Science 110: 533–537.

- Tindall, J. A., H. A. Mills, and D. E. Radcliffe. 1990. The effect of root zone temperature on nutrient uptake of tomato. Journal of Plant Nutrition 13: 939–956. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01904169009364127) (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Weaver, S. E., and C. S. Tan. 1983. Critical period of weed interference in transplanted tomatoes (Lycopersicon esculentum): Growth analysis. Weed Science 31: 476–481. (Available online at: http://www.jstor.org/stable/4043595) (verified 25 Apr 2023).

- Webster, T. M. 2006. Weed survey – southern states. Vegetable, fruit and nut crops subsection. Proceedings of the Southern Weed Science Society 59: 260–277. (Available online at: http://www.swss.ws/wp-content/uploads/docs/2006%20Proceedings-SWSS.pdf) (verified 25 Apr 2023).