eOrganic author:

Mark Schonbeck, Organic Farming Research Foundation, Virginia Association for Biological Farming

Introduction

The following “weed walk” introduces some of our most serious agricultural weeds and their plant families. These plant families also happen to include the majority of the world's food and fiber crops. While this is not a key or identification guide, the information herein is intended to familiarize you with the world of weeds from a taxonomic (identification and genetic relationships) point of view, and to offer examples of some of the features to look for when identifying weeds. Field guides to agricultural weeds commonly organize weeds by plant family, and use the distinguishing characteristics of plant families to help the user narrow down the identity of a particular weed (Bryson & DeFelice, 2009; Old et al., 2008; Uva et al., 1997).

Dicots and Monocots

The world's flowering plants are divided into two sub-classes: the Dicotyledonae (dicots), and the Monocotyledonae (monocots). The plant embryo within the seed of a dicot has two cotyledons (seed leaves), while the plant embryo of a monocot has just one (Fig. 1). When the seed germinates, the embryo becomes a growing seedling, and draws upon food reserves in the cotyledon(s) or the endosperm (a nutrient-rich seed tissue that is not part of the embryo itself) as it develops its first true leaves and an expanding root system. The true leaves often differ greatly from the cotyledons in shape and size.

Dicot seedlings usually have a distinct primary root, which grows vertically down into the soil, sometimes becoming a taproot as the plant grows. Monocot seedlings tend to grow a cluster of several roots spreading out from the site of germination, which branch further to form a fibrous root system (Fig. 1).

Most dicots have variously-shaped leaves that are relatively wide (leaf blade more than 1/10 as wide as long), while most monocots have narrow, linear leaves less than 1/10 as wide as long.

Figure 1. Seedlings of a grass, onion, clover, and mustard. The first two are monocots, in which the cotyledon most often remains below ground, though onion family cotyledons emerge. The last two are dicots, whose cotyledons and growing points usually emerge above the ground, although the cotyledons of peas and vetches remain below ground while the growing points and shoots emerge. Root systems are typically fibrous in monocots, and tap-rooted to a greater or lesser degree in dicots. Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Broadleaf and Grass Weeds

Weed scientists commonly speak of broadleaf and grass weeds, which correspond approximately to the Dicot and Monocot subclasses, respectively. This is a useful characterization, not only in conventional weed control (grasses and broadleaf species have different sensitivities to different chemical herbicides), but also in organic weed management. Grasses and broadleaf weeds respond differently to cultivation, mulching, cover crops, and other practices.

Strictly speaking, the Monocot weeds include sedges, rushes, dayflowers, and wild relatives of onion, garlic, and lilies, as well as true grasses, and are collectively called grass-like weeds.

In addition, a few kinds of non-flowering plants can become weeds. These include field horsetail (Equisetum), mosses, and liverworts, which occur in moist environments in orchard and landscape, turf, and greenhouse container plantings, respectively. They are rarely major weeds in cropland, and will not be discussed further here.

Following is a listing in alphabetical order of 23 plant families that include important agricultural weeds in the United States.

Amaranthaceae—the Amaranth or Pigweed Family (Dicot)

The amaranth family includes several major weeds of vegetables and other cultivated crops. These include smooth pigweed and spiny amaranth, cited as the world's 14th and 15th worst weeds (Holm et al., 1991), as well as redroot pigweed, Palmer amaranth, Powell amaranth, common waterhemp, tall waterhemp, tumble pigweed, and prostrate pigweed, which are common in the United States. Well-adapted to high temperatures, the pigweeds are among the most aggressive of summer annuals and can cause substantial yield losses, even in vigorous crops like sweet corn or tomato. Palmer amaranth and the waterhemps have become particularly troublesome in the southern and midwestern United States because of their rapid development of resistance to glyphosate and their large size. Some amaranths are cultivated for their highly nutritious greens, edible grain, or ornamental flower heads.

Amaranths typically have dense spikes of minute flowers, tiny seeds, simple leaves, and sometimes a distinct reddish coloration of the taproot and lower stem. A single mature pigweed can shed 100,000 to 1 million viable seeds (Fig. 2).

Figure 2. A large pigweed plant with seed heads approaching maturity. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Apiaceae or Umbelliferae—the Carrot or Umbel Family (Dicot)

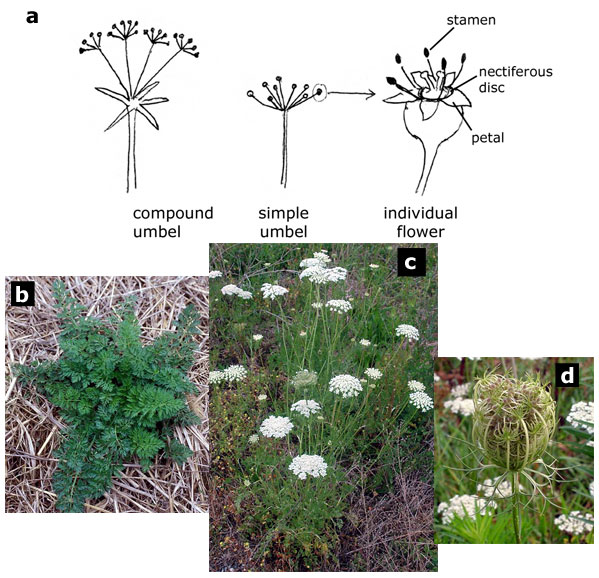

This plant family includes two highly poisonous weeds—poison hemlock and water hemlock—which can be life-threatening to humans or livestock if ingested. The other widely-known weed in this plant family is Queen Anne's lace, or wild carrot (Fig. 3 b–d), a Eurasian species from which the modern vegetable carrot was derived through breeding and selection over the past 2,000 years. Other horticultural crops in this family include celery, celeriac, parsnip, parsley, dill, fennel, cilantro (coriander), caraway, bishop's weed, and many ornamentals. Most members of this plant family provide excellent nectar sources for natural enemies of some insect pests of vegetable crops, and thus have significant economic value in organic insect pest management.

Figure 3. Flowers in the Apiaceae family are arranged in simple or compound umbels (a). Individual flowers have a nectiferous disk, which attracts natural enemies of many insect pests. Wild carrot or Queen Anne's lace (b-d) is a well-known member of this family. During its first year of growth, this biennial forms a basal rosette (b), in contrast to the taller flowering form it takes on in its second year (c). The maturing seed head is shown in (d). Figure credits: (a) Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming; (b) Ohio State Weed Lab Archive, The Ohio State University, Bugwood.org; (c) Chris Evans, River to River CWMA, Bugwood.org; (d) Wendy VanDyk Evans, Bugwood.org.

The key characteristic of the carrot family is the umbel, an inflorescence in which all of the individual flower stalks arise from a single point (Fig. 3). Some species have compound umbels. Other characteristics include highly divided or dissected leaves that may be aromatic, and small, shallow, nectar-rich flowers. Most species in this plant family have a biennial life cycle. Wild carrot sometimes occurs in vegetable fields but more often in pasture or hay fields, and frequently in field margins, where some farmers welcome it as beneficial insect habitat.

Asclepiadaceae—the Milkweed Family (Dicot)

Milkweeds most often occur in field margins and pastures. However, common milkweed can become a weed of vegetable and field crops, especially when reduced tillage or no-till practices are implemented.

Plants in the milkweed family are characterized by the milky sap that exudes from severed stems or leaves. Common milkweed (Fig. 4) is an invasive perennial that propagates through a deep, extensive network of rhizomes, as well as seed. The plant forms tall (up to 6 ft), sparsely-branched stems with opposite, simple leaves, and globular inflorescences or flower heads consisting of up to 100 or more individual flowers.

Figure 4. Common milkweed seedling (a), vegetative shoot emerging from rhizome or rootstock (b), mature plant in flower (c), and close-up of inflorescence (d). Figure credits: (a) Phil Westra, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org; (b) Ohio State Weed Lab Archive, The Ohio State University, Bugwood.org; (c) Phil Westra, Colorado State University, Bugwood.org; (d) Theodore Webster, USDA Agricultural Research Service, Bugwood.org.

Asteraceae or Compositae—the Daisy or Sunflower Family (Dicot)

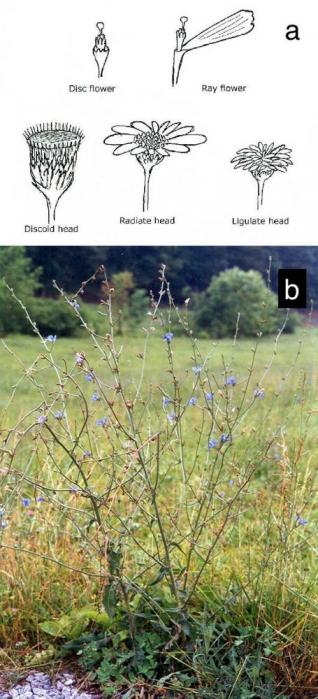

Many members of the large and diverse plant family Asteraceae have become serious agricultural weeds, including common ragweed, Canada thistle, musk thistle, annual sowthistle, prickly lettuce, spotted knapweed, common cocklebur, common dandelion, galinsoga, common yarrow, and others, many of which frequent vegetable fields. Ten of these made the Holm et al. (1991) list of 76 globally important weeds. Crops in this plant family include sunflower, safflower, lettuce, endive, artichoke, zinnia, dahlia, and many other cut flowers and ornamentals.

The most definitive characteristic of the Asteraceae is the inflorescence. What we commonly call a daisy or zinnia flower is actually a head, an inflorescence made up of dozens or hundreds of tiny individual flowers packed together (Fig. 5)—hence the old family name Compositae. The readily-accessible pollen and nectar of the composite flowers make both cultivated and weedy members of this plant family excellent food sources for the adult phases of many beneficial insects, such as parasitic wasps and hoverflies.

Figure 5. What we call the flower of a plant in the composite family is actually a head made up of dozens or hundreds of tiny individual flowers in “disk” and “ray” forms (a). Chicory (b) is a common weed in this plant family with showy blue ligulate (ray only) flower heads. Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

This large plant family includes annuals, biennials, and perennials with or without taproots, rhizomes, or tubers. Many weeds in this family have strongly lobed or divided leaves, which grow in basal rosettes during the vegetative phase of the plant's lifecycle.

Brassicaceae or Cruciferae—the Mustard or Cabbage Family (Dicot)

The mustard family includes a number of common weeds of cool-season vegetables and cereal grains, such as wild mustards, shepherd's purse, and yellow rocket. Garlic mustard is an invasive exotic species of particular concern because its strongly allelopathic properties help it to invade woodlands in the United States. Many of our most important vegetable crops also come from the brassica family, including cabbage, broccoli, cauliflower, kale, collards, bok choy, various cultivated mustards, arugula, and other gourmet greens.

Members of the mustard family have a characteristic flower structure with four petals arranged in a cross, and six stamens. The stamens are arranged in an inner circle of four, and two outer, shorter stamens (Fig. 6). Other characteristics include a distinctive seedpod partitioned lengthwise into two valves that split apart from base to apex at full maturity, and accumulation of pungent, sulfurous compounds called glucosinolates, which have allelopathic and antimicrobial properties.

Figure 6. Brassica plants have a characteristic cotyledon shape with a distinct notch at the apex. The flower has four petals arranged in a cross with six stamens. This plant family includes several winter annual weeds such as shepherd's purse, as well as vegetable crops such as cabbage and broccoli. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

The mustard family consists of herbaceous plants of cool to temperate climates. While the weedy members of this family are well known and sometimes troublesome to vegetable growers, only one—shepherd's purse—is listed among the world's 76 major weeds (Holm et al., 1991). Brassica weeds can be a reservoir of pests and diseases of related vegetable crops, yet flowering brassicas (weedy or cultivated) often attract the natural enemies of the brassica pest complex.

Caryophyllaceae—the Pink Family (Dicot)

The pink family includes common chickweed, mouse-ear chickweed, corn spurry, and corn cockle, as well as ornamental flowers such as carnation, pinks, sweet William, baby's breath, and Maltese cross. Common chickweed is particularly troublesome in garlic, early greens, other cool season vegetables, and cool-season forage crops, but it usually does not seriously impact warm-season vegetable or row crops.

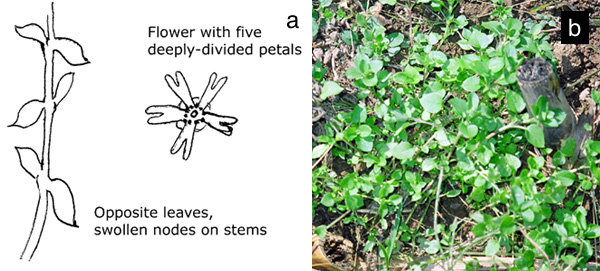

The pink family is characterized by simple, opposite leaves arising from swollen nodes, regular flowers, usually with five petals, but sometime with the petals deeply notched or lobed to give the appearance of 10 petals per bloom, as seen in the chickweeds (Fig. 7).

Figure 7. Weeds in the pink family have oppositely-arranged leaves, and small five-petaled flowers with the petals deeply lobed, giving the appearance of 4(a). Common chickweed (b) is a widespread winter annual or occasionally perennial weed in this family. Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Chenopodiaceae—the Goosefoot Family (Dicot)

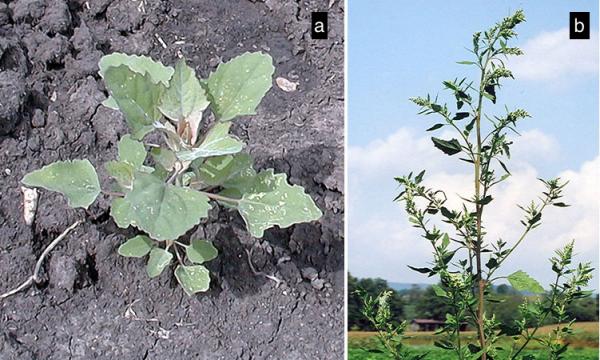

Common lambsquarters, whose young foliage is edible and as nutritious as spinach, chard, and beet (also members of the goosefoot family), hardly needs introduction to vegetable and grain farmers (Fig. 8). Considered the world's tenth worst weed (Holm et al., 1991), lambsquarters can be an aggressive spring or summer annual weed in croplands in temperate regions around the world. It is highly prolific, and one large plant can shed 50-100,000 viable seeds.

Figure 8. Young (a) and mature (b) lambsquarters plants. Figure credits: left: Ed Zaborski, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign; right: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Kochia is another summer annual weed in the goosefoot family. It has become a problem in annual crops in the northern Great Plains region.

Commelinaceae—the Spiderwort Family (Monocot)

Dayflowers are often mistaken for dicots because their leaves are wider than those of most monocots. They have three-petaled blue to purple flowers (in some species, one petal is smaller and paler than the other two), with six stamens. Asiatic dayflower and spreading dayflower are sprawling summer annual herbs that have become naturalized in moist soils near streams and bottomland woods throughout the eastern United States. They are occasional weeds of gardens and fields. A more recent and more invasive introduction is the Benghal dayflower, which spreads aggressively by rhizomes, and can form flowers and seeds either above or below ground. It has become a severe problem in cotton and other crops in parts of Florida and the Gulf Coast.

Figure 9. Asiatic dayflower (a) and Benghal dayflower (b). Figure credits: (a) Wendy VanDyk Evans, Bugwood.org, (b) Herb Pilcher, USDA ARS, Bugwood.org.

Convolvulaceae—the Morning Glory Family (Dicot)

The morning glory family includes the incredibly deep-rooted (3 to 18 feet) wandering perennial field bindweed, recognized as the world's 12th most damaging weed (Holm et al., 1991); the slightly less deep-rooted yet still highly invasive hedge bindweed (Fig. 10a–b), and several summer annual morning glories that frequent vegetable and row crops in the South and Midwest. The parasitic dodders are also members of this plant family.

Figure 10. Hedge bindweed climbs this fence and covers the ground between clumps of grass weeds (a). Uprooted bindweed shows the vining habit and the underground network of brittle, white fleshy rhizomes (b). The one-inch fragment separated from the rest of the plant can regenerate a new plant from as deep as six inches. Ivyleaf morning glory (c) and tall morning glory (d) are two species of weedy annual morning glory that commonly occur in vegetable and row crops in warm-temperate climates. Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Family characteristics include showy, funnel- or tube-shaped flowers, simple alternate leaves, and a climbing, vine-like habit of growth. Many of these weeds climb any upright support, including crop plants, whose growth and leaf opening can become seriously hindered as a result. Weeds in the Convolvulaceae thrive in summer heat, as does the sweet potato, one important food crop in this family. Sweet potato vines do not climb, but instead form a thick canopy, which effectively suppresses many weeds including yellow nutsedge.

Cyperaceae—the Sedge Family (Monocot)

While this family includes no major crops in the United States, and only a few weed species, one of the latter is purple nutsedge, once cited as the world's worst weed (Holm et al., 1991). This small, heat-loving plant causes serious economic losses in most tropical and warm-temperate crops around the world. A wandering perennial, purple nutsedge is highly allelopathic against many crops, and can form an underground biomass density of rhizomes, bulbs, and tubers that rivals or exceeds the total biomass of a vigorous 9-ft crop of sorghum.

Yellow nutsedge is also quite aggressive and has invaded colder regions up to the Canadian border. Holm et al. (1991) list yellow nutsedge as the world's 16th most costly weed. Cultivated strains of yellow nutsedge are grown in India for their edible tubers (chuffa).

Sedges are characterized by grass-like leaves deployed in a three-ranked arrangement, and solid stems distinctly triangular in cross section (Fig. 11). In contrast, true grasses have rounded stems, which are hollow between the nodes, and leaves in a two-ranked arrangement.

Figure 11. Sedges are characterized by leaves arranged in three ranks around a solid, triangular stem (a), whereas true grasses have two-ranked leaf arrangement and hollow, cylindrical stems. This vigorous yellow nutsedge shoot (b) arises from a tuber in the top few inches of soil. Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Euphorbiaceae—the Spurge Family (Dicot)

Cypress spurge (Fig. 12) is a major weed of vegetable and row crops in the northeastern United States. Other common weeds in this family include leafy spurge (a major rangeland weed in the western United States), Virginia copperleaf, wooly croton, and spotted spurge. One of the characteristics of this plant family is the acrid, milky juice exuded from cut tissues, which can be a severe eye irritant. Flowers are small and inconspicuous, often imperfect (stamens and pistils borne on separate flowers), and often lacking petals. In many species, several flowers are grouped together in a cuplike structure, which itself resembles a flower.

Figure 12. Cypress spurge, Euphorbia cyparissias L. Figure credit: Richard Old, XID Services, Inc., Bugwood.org.

Fabaceae or Leguminosae—the Legume Family (Dicot)

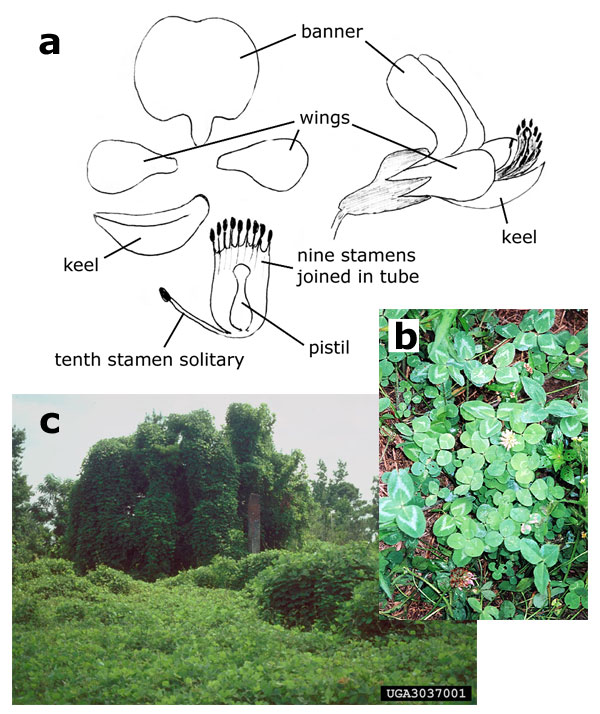

The legume family plays a special role in organic and sustainable agriculture, as these plants fix atmospheric nitrogen (N) through their symbiotic relationship with Rhizobium bacteria. Legumes provide protein-rich beans, peas, pulses, and livestock forages such as alfalfa, clovers, and lespedeza. This plant family includes a few summer annual weeds, such as hemp sesbania, and showy crotolaria, as well as kudzu, a highly invasive exotic perennial vine, which can overgrow and kill mature forest trees (Fig. 13c).

In addition to their N-fixing root nodules, legumes typically have compound leaves (trifoliate, pinnate, or palmate), and bear seeds in pods that dry and split open along both sutures. Many legumes have characteristic pea blossoms with petals differentiated into banner, wings, and keel; and 10 stamens with the filaments of 9 or all 10 fused into a strap or tube (Fig. 13a).

Figure 13. Many legumes have a characteristic pea flower (a), though some species such as mimosa have more regular flowers. Weeds in this family range from white clover (b) causing occasional problems in low-growing vegetables, to kudzu (c) smothering mature trees. Figure credits: (a) and (b), Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming; (c) Robert L. Anderson, USDA Forest Service, Bugwood.org.

Lamiaceae or Labiatae—the Mint Family (Dicot)

The Lamiaceae includes several winter annual and perennial weeds, including purple deadnettle (Fig. 14a), and ground ivy (Fig. 14b), as well as many of our culinary herbs such as basil, oregano, sage, thyme, and mint. The mint family is characterized by aromatic foliage rich in essential oils, opposite leaves borne on stems that are square in cross section, and usually a distinctly bilabiate flower with four stamens. The flowers are rich in nectar and often attract and support natural enemies of insect pests.

Figure 14. Common weeds in the mint family include the winter annual purple deadnettle (a) and the perennial ground ivy (b). Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Weedy members of this family that are familiar to vegetable and grain growers include henbit, deadnettles, and ground ivy. Mint itself can become a troublesome weed, as its perennial rhizomes readily spread from the mint patch into neighboring crops.

Malvaceae—the Mallow or Cotton Family (Dicot)

The mallow family includes the summer annual weeds velvetleaf, prickly sida, and spurred anoda, as well as the perennial common mallow. Velvetleaf is a major weed of corn and other row crops, especially in fields that are plowed annually. The mallow family also includes several important crops: cotton, okra, kenaf, hibiscus, and ornamental mallows.

The mallow family is characterized by showy flowers with five sepals, five petals, and numerous stamens whose filaments are fused into a tube surrounding the style of the pistil. Emerging seedlings of some species bear one roundish and one distinctly heart-shaped cotyledon (Fig. 15).

Figure 15. (a) Seedlings of some species in the mallow family have one roundish and one heart-shaped cotyledon. The flower has numerous stamens fused into a tube surrounding the pistil. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming. (b) Velvetleaf, Abutilon theophrasti. Figure credit: Bruce Ackley, The Ohio State University, Bugwood.org.

Oxalidaceae—the Oxalis Family (Dicot)

Yellow woodsorrel (Fig. 16) is a small rhizomatous perennial weed with yellow flowers. While it is most often a weed of turf, landscapes, and greenhouse plants, it can occur in vegetable fields, especially under reduced tillage. It has trifoliate compound leaves, and small, regular flowers with five yellow petals.

Figure 16. Yellow woodsorrel, Oxalis stricta L.—also known as common oxalis. Figure credit: Ted Bodner, Southern Weed Science Society, Bugwood.org.

Phytolaccaceae—the Pokeweed Family (Dicot)

Pokeweed is a well-known and spectacular herbaceous perennial. It comes up from heavy fleshy taproots every spring and can grow as tall as 10 feet (Fig. 17). It bears small white or pink flowers on racemes up to 12 inches long, and forms black berries 1/4 to 1/2 inch across. The foliage and berries are poisonous to humans and livestock, though newly emerging foliage can be eaten if properly prepared.

Figure 17. American pokeweed, Phytolacca americana L. Figure credit: Ed Zaborski, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Plantaginaceae—the Plantain Family (Dicot)

The plantain family includes several weedy species, such as broadleaf plantain and buckhorn plantain, which are most troublesome in turfgrass, though they can occur in cultivated fields and gardens as well. The weedy plantains are low-growing perennials characterized by parallel leaf veins (unusual in dicots). The sessile (without petiole) leaves grow in a basal rosette, from which arises a leafless stalk bearing a dense spike of tiny, inconspicuously colored flowers (Fig. 18).

Figure 18. Broadleaf or common plantain, Plantago major L. Figure credit: John Cardina, The Ohio State University, Bugwood.org.

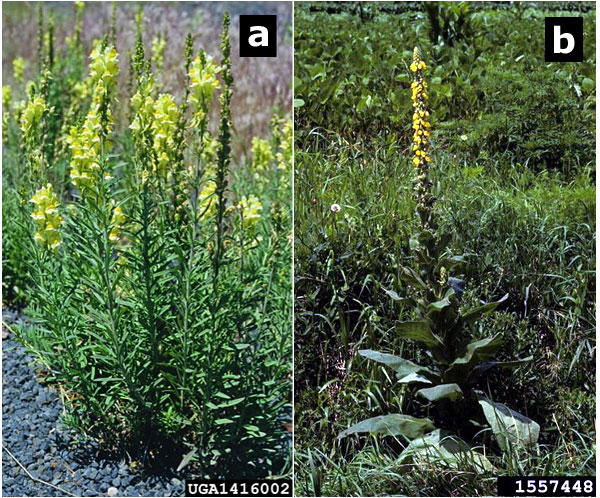

This plant family also includes plants that were formerly classified in the Scrophulariaceae or Figwort family, such as yellow toadflax (Fig. 19a), common mullein (Fig. 19b), and several species of speedwell that occasionally occur in vegetable crops, as well as ornamental flowers such as snapdragon.

Figure 19. (a) Yellow toadflax, Linaria vulgaris P. Mill. (b) Common mullein, Verbascum thapsus L. Figure credits: (a) Linda Wilson, University of Idaho, Bugwood.org; (b) John Cardina, The Ohio State University, Bugwood.org.

Poaceae or Gramineae—the Grass Family (Monocot)

The grasses comprise a large family of monocots—clearly the most agriculturally important plant family on Earth. In addition to many of the world's staple food and fodder crops (corn, rice, wheat, millets, sorghums, other annual cereal grains; and many perennial and annual forages), the grass family contributes 29 of the 76 species listed as the most important agricultural weeds worldwide, including 10 of the top 18 (Holm, et al., 1991). Bermuda grass, barnyard grass, jungle rice, goosegrass (Fig. 20a), johnsongrass (Fig. 20b), and large crabgrass—which are all too familiar to farmers in the United States—take second, third, fourth, fifth, sixth, and eleventh places in this listing. The weedy species include both annuals (e.g., barnyard grass, goosegrass, crabgrasses, foxtails) and perennials (e.g., Bermuda grass, johnsongrass, quackgrass).

Figure 20. Two major weeds in the grass family include goosegrass (a) and johnsongrass (b). Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

The most definitive characteristics of grasses are that the single cotyledon remains underground inside the seed after germination, and that the seedling shoot emerges as a rolled or folded set of leaf blades protected by a sheath (coleoptile) that opens at the soil surface to release the expanding leaf blades. The growing point remains underground for some weeks after emergence unlike broadleaf plants (Fig. 21); thus the young grass plant is not killed by frost, heat, mowing, or removal of aboveground parts. As a result, young annual grass weeds are more difficult to control by cultivation or flame weeding than annual broadleaf weeds of the same size. Mulching is also less effective on grasses than other weed seedlings, as the coleoptiles can penetrate organic mulches more readily than the delicate shoots of broadleaf seedlings.

Figure 21. Grass seedlings emerge as a pointed coleoptile, which protects the new leaves as the seedling pushes through the soil and surface residues. The growing point remains below ground for several weeks and can regenerate the plant if the top is severed or frozen. Most broadleaf seedlings bring both growing point and cotyledons above the soil surface upon germination, leaving them more vulnerable to cultivation or unfavorable weather conditions such as frost. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Other grass characteristics include narrow, linear leaves (often 20-50 times as long as wide); small, inconspicuous flowers borne on a spike or panicle at the top of the stem, small dry fruits each containing a single seed or grain, and a strong, fibrous root system. Perennial grasses may or may not have stolons or rhizomes, but never taproots. Quack grass, Bermuda grass, and johnsongrass are all wandering (creeping) perennials that propagate through strong, aggressive rhizomes or stolons.

Polygonaceae—the Buckwheat Family (Dicot)

The buckwheat family includes the knotweeds, smartweeds, curly dock, broadleaf dock, and red sorrel, as well as buckwheat, a valuable grain and cover crop. Wild buckwheat and mile-a-minute are rampant annual vines that climb, shade, and bind other plants much like bindweeds and morning glories. The docks and wild buckwheat are considered among the 76 globally important weeds cited by Holm et al. (1991).

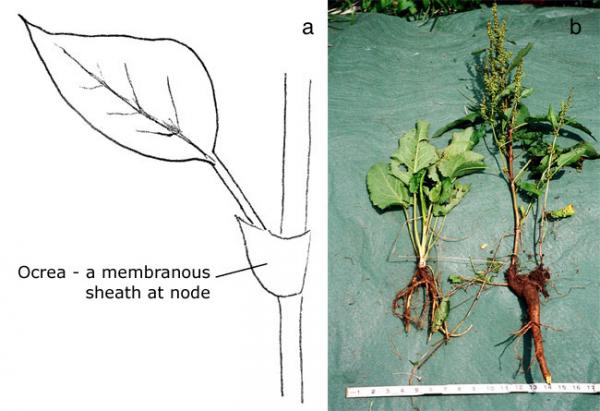

One distinguishing characteristic of the buckwheat family is the ocrea, a prominent membranous or leafy sheath encircling the stem and base of the petiole at each node (Fig. 22a). Other traits include small flowers, which may be white, greenish, or brightly colored; simple leaves with mostly smooth (entire) edges, and a small, dry, single-seeded fruit, which is often three-sided or angular.

Figure 22. Plants in the buckwheat family have a characteristic membranous sheath around each leaf node (a). Broadleaf dock and curly dock (b) are taprooted perennial weeds in this family. Figure credits: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Some species, notably buckwheat and smartweeds, have plentiful nectar that can attract and support beneficial insects.

Portulacaceae—the Purslane Family (Dicot)

Common purslane is an edible, succulent summer annual weed (Fig. 23), which grows in prostrate mats and can compete severely with young or low-growing crops. It is hard to control by cultivation, as broken fragments of this drought-tolerant weed re-root readily and grow into new plants. These traits, combined with its worldwide distribution, have earned it the dubious honor of being the world's ninth worst weed (Holm et al., 1991). Cultivated members of this family include ornamental flowering portulacas as well as some domesticated varieties of purslane grown as a salad green.

Figure 23. Common purslane is edible and highly nutritious. It does not compete aggressively when it grows as an understory in tall, established crops such as sweet corn or tomato, but it can be a major problem during crop seedling establishment and in slow-growing vegetables like carrot or onion. Figure credits: a: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming; b: Ed Zaborski, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

Rosaceae—the Rose Family (Dicot)

The rose family includes many of our most important fruit crops—strawberries, brambles, apples, pears, peaches, and other stone fruit—as well as almonds, cultivated roses, and some other ornamental crops. Multiflora rose escaped from early colonial gardens to become a serious pasture weed. Wild blackberries and other wild brambles are sometimes considered weeds, and sometimes welcomed as a wild food source. Vegetable growers encounter multiflora and brambles mainly when they first convert pasture, hayfield, or brushy land to vegetable production. The cinquefoils are low-growing herbaceous perennial weeds in this plant family, which are usually only a minor problem in cropland.

Characteristics of the rose family include alternate leaves, regular flowers with five sepals, five petals, and many stamens in several whorls. (Cultivated roses have been bred/selected to have many petals per flower.) The family includes perennial trees, shrubs, and herbs, many of which are armed with thorns or prickles.

Rubiaceae—the Madder Family

This plant family includes one major weed of winter grain crops: cleavers, otherwise known as catchweed bedstraw (Fig. 24). It is not considered a major weed in vegetable production.

Figure 24. Cleavers, Galium aparine L. Figure credits: (a) Steve Dewey, Utah State University, Bugwood.org; (b) Ted Bodner, Southern Weed Science Society, Bugwood.org (links verified 26 Nov 2008).

Solanaceae—the Nightshade or Tomato Family (Dicot)

The nightshade family includes several toxic weeds such as the summer annuals jimsonweed and black nightshade, and the rhizomatous perennial weed horsenettle (Fig. 25), which likes to leave its tiny, irritating spines in farmworkers' hands. Major food crops in this family include potato, tomato, sweet and hot peppers, and eggplant. In addition to competing for nutrients and moisture, nightshade weeds in vegetable fields can be a reservoir of pests or diseases of these crops.

Figure 25. Horsenettle, shown here in pasture, can also occur in vegetable fields, especially those recently converted from sod or managed with reduced tillage. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

The nightshade family is characterized by regular (symmetrical) flowers with five petals partially or fully fused into a tube or bell-shaped corolla, fleshy fruits (berries), and usually simple leaves. In most species, the foliage accumulates toxic alkaloids and can be dangerous if ingested by livestock or humans. If the dark, fleshy fruits (berries) of black nightshades contaminate vegetable seed (pea or bean) crops during harvest, they can stain the seeds and render them unmarketable.

This article is part of a series on Twelve Steps Toward Ecological Weed Management in Organic Vegetables. For more on weed monitoring and identification, see:

References and Citations

- Bryson, C. T., and Michael S. DeFelice (ed.). 2009. Weeds of the South. Photography by Arlyn W. Evans. University of Georgia Press, Athens, GA.

- Holm, L. G., D. L. Plucknett, J. V. Pancho, and J. P. Herberger. 1991. The world's worst weeds: Distribution and biology. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, FL.

- Old, R. 2008. 1,200 weeds of the 48 states and adjacent Canada: An interactive identification guide [DVD]. XID Services, Inc., Pullman, WA. http://xidservices.com/.

- Uva, R. H., J. C. Neal and J. M. DiTomaso. 1997. Weeds of the Northeast. Cornell University Press, Ithaca, NY.

Appendix: Latin Names and Life Cycle Category of Weeds Mentioned in Text

- Amaranth, Palmer – Amaranthus palmeri – summer annual

- Amaranth, Powell – Amaranthus powellii – summer annual

- Amaranth, spiny – Amaranthus spinosus – summer annual

- Anoda, spurred – Anoda cristata – summer annual

- Barnyardgrass – Echinocloa crus-galli – summer annual

- Bermudagrass – Dactylon cynodon – stoloniferous perennial

- Bindweed, field – Convovulus arvensis – rhizomatous perennial

- Bindweed, hedge – Calystegia sepium – rhizomatous perennial

- Brambles – Rubus spp. – perennial

- Buckwheat, wild – Polygonum convolvulus – summer annual

- Carrot, wild (= Queen Anne’s lace) – Daucus carota – biennial

- Chicory – Cichorium intybus – simple perennial

- Chickweed, common – Stellaria media – winter annual

- Chickweed, mouse-ear – Cerastium fontanum ssp. vulgare (= C. vulgatum) - perennial

- Cinquefoils – Potentilla spp.- perennial

- Cockle, corn – Agrostemma githago – winter annual or biennial

- Cocklebur, common – Xanthium strumarium – summer annual

- Copperleaf, Virginia – Acalypha virginica – summer annual

- Crabgrass, large – Digitaria sanguinalis – summer annual

- Crotolaria, showy – Crotolaria spectabilis – summer annual

- Croton, wooly – Croton capitatus – annual

- Dandelion, common – Taraxicum officinale – simple perennial

- Dayflower, Asiatic or common – Commelina communis – summer annual

- Dayflower, Benghal – Commelina benghalensis – rhizomatous perennial or annual

- Dayflower, spreading – Commelina diffusa – summer annual

- Deadnettle, purple – Lamium purpureum – winter annual

- Dock, broadleaf – Rumex obtusifolius – simple perennial

- Dock, curly – Rumex crispus – simple perennial

- Dodder – Cuscuta spp. – plant-parasitic annual

- Foxtails – Setaria spp. – summer annual

- Galinsoga, hairy – Galinsoga quadriradiata (= G. ciliata) – summer annual

- Galinsoga, smallflower – Galinsoga parviflora – summer annual

- Garlic Mustard - Alliaria petiolata - biennial

- Goosegrass – Eleusine indica – summer annual

- Ground ivy – Glechoma hederacea – stoloniferous perennial

- Hemlock, poison – Conium maculatum – biennial

- Hemlock, water – Cicuta maculata – perennial

- Henbit – Lamium amplexicaule – winter annual or biennial

- Horsenettle – Solanum carolinense – rhizomatous perennial

- Horsetail, field – Equisetum arvense – perennial

- Jimsonweed – Datura stramonium – summer annual

- Johnsongrass – Sorghum halepense – rhizomatous perennial

- Jungle rice – Echinocloa colona – summer annual

- Knapweed, spotted – Centaurea biebersteinii (= C. maculosa) – biennial or simple perennial

- Knotweeds – Polygonum spp. – mostly annuals

- Kochia – Kochia scoparia – spring-summer annual

- Kudzu – Pueraria lobata – rhizomatous and tuberous perennial

- Lambsquarters, common – Chenopodium album – spring/summer annual

- Lettuce, prickly – Lactuca serriola – winter annual or biennial

- Mallow, common – Malva neglecta – winter annual or biennial

- Mile-a-minute – Polygonum perfoliatum – summer annual

- Milkweed, common – Asclepias seriaca – rhizomatous perennial

- Morning glories – Ipomoea spp. – mostly annuals

- Morning glory, ivyleaf – Ipomoea hederifolia – summer annual

- Morning glory, tall – Ipomoea purpurea – summer annual

- Mustards, wild – Brassica spp. and Sinapis arvensis – winter annuals

- Nightshade, black – Solanum spp. – summer annual

- Nutsedge, purple – Cyperus rotundus – rhizomatous & tuber-forming perennial

- Nutsedge, yellow – Cyperus esculentus – rhizomatous & tuber-forming perennial

- Pigweed, prostrate – Amaranthus blitoides – summer annual

- Pigweed, redroot – Amaranthus retroflexus – summer annual

- Pigweeds, smooth – Amaranthus hybridus – summer annual

- Pigweed, tumble – Amaranthus albus – summer annual

- Plantain, broadleaf – Plantago major – simple perennial

- Plantain, buckhorn – Plantago lanceolata – simple perennial

- Pokeweed, common – Phytolacca americana – simple perennial

- Purslane, common – Portulaca oleracea – summer annual

- Quackgrass – Elymus repens (= Elytrigia repens) – rhizomatous perennial

- Ragweed, common – Ambrosia artemesiifolia – summer annual

- Rose, multiflora – Rosa multiflora - perennial

- Sesbania, hemp - Sesbanea herbacea – summer annual

- Shepherd’s-purse – Capsella bursa-pastoris – winter annual

- Smartweeds – Polygonum spp. – summer annuals

- Sida, prickly – Sida spinosa – summer annual

- Spurge, cypress – Euphorbia cyparissias – root-propagating perennial

- Spurge, leafy – Euphorbia escula – root-propagating perennial

- Spurge, spotted – Chamaescyce maculata (= Euphorbia maculata) - annual

- Spurry, corn – Spergula arvensis - annual

- Sowthistle, annual – (Sonchus oleraceus and S. asper) – winter annual

- Thistle, Canada – Cirsium arvense – rhizomatous perennial

- Thistle, musk – Carduus nutans – biennial

- Toadflax, common or yellow – Linaria vulgaris – root-propagating perennial

- Velvetleaf – Abutilon theophrasti – summer annual

- Waterhemp, common – Amaranthus rudis – summer annual

- Waterhemp, tall – Amaranthus tuberculatus – summer annual

- Witchweed – Striga asiatica – plant-parasitic annual

- Wood Sorrel, yellow – Oxalis stricta – rhizomatous perennial

- Yarrow, common – Achillea millefolium - perennial

- Yellow rocket – Barbarea vulgaris – winter annual or biennial