eOrganic author:

Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming

Introduction

Effective organic weed management begins with monitoring weeds to assess current or potential threats to crop production, and to determine best methods and timing for control measures (Fig. 1). Regular monitoring of each field allows the farmer to:

- Spot critical stages of crop and weed development for timely cultivation or other intervention.

- Identify the weed flora (species composition), which helps determine best short- and long-term management strategies.

- Detect new invasive or aggressive weed species while the infestation is still localized and possible to eradicate.

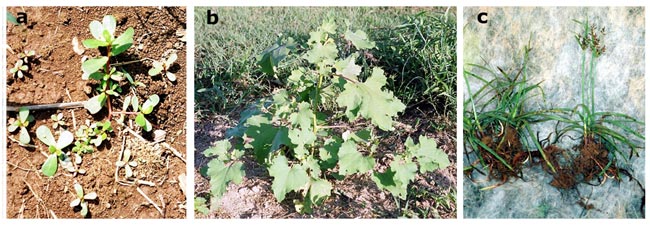

Figure 1. (a) This flush of pigweed, galinsoga, purslane and other summer annual weed seedlings can be controlled through timely cultivation or flame weeding, followed by mulching to hinder additional weed emergence. Cultivate or flame now before the weeds get any larger and more resistant to these tactics. Long-term management strategies might include reducing tillage, or rotating the field into fast-growing spring or summer cover crops followed by fall vegetables. (b) These vigorous, spiny shoots of Canada thistle emerged, not from seed, but from rootstocks or fragments thereof left by spring tillage. If this is a new, localized infestation, focused efforts to eradicate the new invader by repeated hoeing or tillage and planting the patch with competitive cover crops will save much greater weed management costs in future years. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

The weed scout watches for critical aspects of the weed-crop interaction, such as:

- Weed seed germination and seedling emergence

- Weed growth sufficient to affect crops if left unchecked

- Weed density, height, and cover relative to crop height, cover, and stage of growth

- Weed impacts on crops, including harboring pests, pathogens, or beneficial organisms; or modifying microclimate, air circulation, or soil conditions; as well as direct competition for light, nutrients, and moisture

- Flowering, seed set, or vegetative reproduction in weeds

- Efficacy of cultivations and other weed management practices

Information gathered through regular and timely field monitoring helps growers select the best tools and timing for weed control tactics. Missing vital cues in weed and crop development can lead to costly efforts to rescue a vegetable crop through repeated cultivations, which may not be fully effective. Good field scouting can help the grower get the most effective weed control for the least fuel, labor, and soil disturbance.

Are Economic Thresholds Applicable to Weeds?

Current field scouting protocols for many insect pests and some crop diseases compare observed pest levels with research-based economic thresholds (ETs) to determine whether control measures are needed. The ET is the pest population density or level of visible crop damage at which treatment is needed to prevent a net economic loss—a decrease in marketable yield of greater dollar value than the cost of the treatment. The use of ETs to determine whether and when control measures are needed can save money and reduce adverse environmental impacts.

Researchers have attempted to develop ETs for weed management to help growers reduce the use of herbicides, tillage, and cultivation. However, several factors have hampered this effort. Unlike insect or disease outbreaks, which usually involve only one or two species of harmful organism attacking a specific crop, weed growth is usually comprised of several or many species competing with all crops. Weed species differ greatly in height, spread and impacts on crops; hence ETs in terms of weed population density are almost impossible to define (Fig. 2). For example, as few as one pigweed, velvetleaf, or cocklebur plant per 10 row-feet can measurably reduce soybean or corn yields, whereas low growing weeds like purslane, galinsoga, or carpetweed may have little impact on these crops, even at one weed per row-foot. In addition, the population density of a wandering perennial that sends up many shoots from a single underground system of roots and rhizomes defies definition.

Figure 2. Trying to establish an “economic threshold” based on weed counts is not practical. For instance, how many common purslane plants (a) would have the same impact as one common cocklebur (b)? Would this purple nutsedge clump (c) count as one, two, or twenty? Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Studies have shown that the relative leaf area of the weeds present in a crop during the critical period of weed competition, early in crop development, is a better predictor than weed population density of whether and how severely the weeds might reduce yield if left uncontrolled. The relative leaf area of weeds is defined as the weed leaf area divided by the total (weed + crop) leaf area, which can be estimated by field observations. However, the relationship between relative leaf area and potential impact on crop yield varies greatly, depending on when the weeds emerge relative to crop emergence, when in the crop’s life cycle the relative leaf area is measured, the relative heights of weed and crop at maturity, and other factors such as allelopathic relationships between the specific crops and weeds in question. For example, common purslane, which often has little impact on corn yield, can seriously impact low-growing vegetables, especially if weed and vegetable emerge together. Purple nutsedge is also low-growing, but it is so intensely allelopathic, and forms such a large underground biomass, that it can severely damage crops many times its height, especially in tropical climates that favor this weed.

Weed impacts on a given crop vary widely with site-specific factors such as climate, soil conditions, available nutrient levels, and size of the weed seed bank. As a result, it may not be feasible to develop widely applicable action thresholds based on weed numbers, weed biomass or relative leaf area, even for a single weed–crop pair such as lamb's-quarter in tomato. Developing site-specific action thresholds can make a fascinating scientific study, but it is not practical for the busy farmer! Organic farmers need much more practical guidelines, such as those developed by Dr. Charles Mohler of Cornell University (see sidebar).

Sidebar: A Few Simple Guidelines for Knowing When and How to Cultivate

(Charles Mohler, Cornell University, personal communication)

- If you can see any cotyledons out at all when down on hands and knees, it's time to rotary hoe.

- If many weeds are up with unfurled cotyledons and you can see the first true leaf just starting to poke out on any individuals, you shouldn't wait any longer to tine weed (though earlier may work just as well).

- It is never too late to tine weed, provided the crop will tolerate it and you have a weeder that is appropriate for the crop (for example, don't use a weeder with an 85 degree bend in the tines after corn is up). A late tine weeding is often better than none—you won't get all of the weeds, but you can at least thin them out in the row. For example, last year we had a long rainy period after soybean planting, and I couldn't tine weeds for a month after planting. I tine weeded aggressively at the first trifoliate and then came back with a row-crop cultivator the same day and threw ~1 inch of soil into the row while a lot of the weeds were still lying over. Some ragweed got through, but the weed control was fairly decent considering the late timing and heavy weed pressure.

- First row cultivation should come while the weeds are still small enough to bury them by throwing soil into the row. This obviously depends on both what the crop will tolerate and the size of the weeds.

- Cultivate before the weeds get larger than 2-3 inches. Larger weeds will tend to re-root.

In insect or disease IPM, the use of ETs can guide farmers not to spray at all in those seasons when the pest or pathogen is scarce or absent. However, since weeds reliably occur every year in annual cropping systems, the question becomes not whether to act, but when. One weed management tool that has served organic farmers better than ETs is the concept of minimum weed-free period—the period after emergence when a given crop must be kept weed-free to prevent yield losses to weeds. This concept is explored further later in this article.

One limitation of both ETs and minimum weed-free period is that weeds that do not hurt the current crop can still reproduce prolifically, creating much greater weed pressure in coming seasons. Weed scientists have attempted to develop economic optimum thresholds that take into account effects on both current and future cropping seasons. This view has led, in turn, to a no-seed threshold (prevention of any and all weed seed production), which is a basic principle of weed seed bank management.

Why Scout for Weeds so Small you can Hardly See Them?

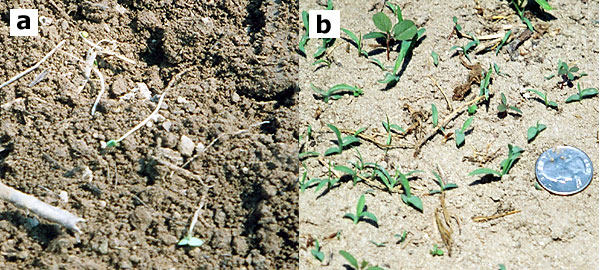

Does weed monitoring include getting down on your hands and knees to look for weeds that are barely large enough to see? You bet it does! It always pays to examine a seedbed to make sure that it does not harbor thousands of germinating weeds that could get the jump on your crop—especially if the seedbed was prepared several days before planting. Lightly stir the soil surface in a few spots throughout the field and look for weeds in the white thread stage (Fig. 3a.; uprooted seedlings look like tiny white threads). If they are there, plan on shallow whole-field cultivation just before planting or just before crop emergence to nip the problem in the bud.

Continue monitoring for emerging weeds throughout the early stages of crop establishment, and plan appropriate control measures based on relative stages of weed and crop development. Remember that these early-emerging weeds have the greatest potential impact on crop yield.

Weeds do not actually begin affecting most vegetable crops until a few weeks after emergence (the beginning of the critical period for weed control). However, it is often more economical to knock weeds out in the white thread stage (Fig. 3a), or at least before they reach a height of one inch (Fig. 3b), than to wait until the weeds are larger. Very shallow cultivation can destroy small weeds, and costs less, does less damage to soil quality and stimulates fewer additional weed seeds to germinate than the deeper, more aggressive cultivation required for larger weeds. If weeds growing near the crop become large enough, it can become virtually impossible to kill them by mechanical cultivation without seriously damaging the crop (Fig. 4). Finally, hot sun rapidly kills tiny uprooted weeds, whereas larger weeds are more apt to re-root and resume growth after cultivation.

Figure 3. These tiny, “white thread” weed seedlings (a) were revealed by lightly brushing the soil surface with fingertips, and will die within a few hours’ exposure to the sun. Tractor-drawn cultivation tools such as tine weeders and basket weeders disturb the soil surface in a similar manner, and can effectively weed several acres per hour if the weeds are small (no more than one inch of aboveground growth). Early cultivation is especially important for grass weeds (b), as their growing points remain below ground and the weed must be uprooted in order to kill it. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Figure 4. The weeds growing with this young sweet corn are just beginning to compete with the crop. Prompt action can prevent significant yield loss; however, it may be very difficult to control these weeds by mechanized cultivation without damaging the crop. At a small scale, this situation means a few hours’ extra manual labor. At a multi-acre scale, it could necessitate tilling up the entire field and replanting. Scouting this field just a week earlier could have led to timely cultivation while weeds were still small and easier to manage. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Scout small weeds to determine whether and when flame weeding might be appropriate. Flaming saves soil and avoids tillage-stimulated weed germination. It is most effective when the weeds’ growing points have emerged above the soil surface and the weeds are still small. Grass weeds are difficult to flame-kill because their growing point remains below ground for several weeks after germination. Consider flaming when most of the weed flora consists of broadleaf species with exposed growing points, and the weeds are up but are not more than two inches tall, with at most two to four leaves above the cotyledons (seed leaves) as shown in Fig. 1a above.

Later-season Weed Management

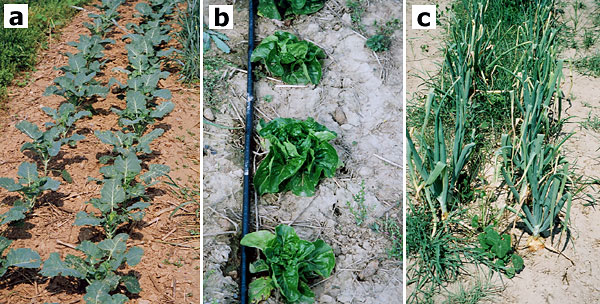

Once the crop is established, how often should later-emerging weeds be removed? Weekly cultivations can keep the crop beautifully clean, but the costs in labor, fuel, and losses of soil organic matter and tilth can outweigh any yield benefits. Allowing some weed growth, usually with one or a few additional timely interventions (cultivation, mowing, mulching, or manual weeding) to protect the current crop and prevent weeds from setting seeds, may be more practical (Fig. 5). Vigorous, fast-growing vegetables that close canopy quickly are less prone to weed competition than slower growing crops, and thus require fewer interventions at this stage.

Figure 5. These crops are old enough not to need as much effort to keep them weed free. The broccoli (a) is far enough ahead of the tiny weeds just emerging in the bed. Larger weeds and cover crop regrowth in alleys can be controlled by mowing. The lettuce (b) is about two weeks from maturity. Prompt tillage after harvest will be sufficient to control the weeds present. Weeds were allowed to grow during the last few weeks’ growth of this onion crop (c). These weeds came in late enough not to hurt onion yield significantly, and were tilled in promptly after onion harvest. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

There are no simple formulas for when additional weed control is needed. Weather conditions can favor the crop over the weeds in one season, and vice versa the next. Weed species differ considerably in how aggressively they impact the crop, and how quickly they propagate themselves for the following season. A particular weed’s aggressiveness also varies with climate and soil. Through careful observation and record keeping over several years, the organic grower can develop site-specific criteria to discern when weed control measures are needed to maintain good yields in each vegetable, and to prevent or limit inputs into the weed seed bank.

Minimum Weed-free Period

The later a weed emerges relative to the crop, the less severely it can impact yield. Weeds that emerge after a crop’s minimum weed-free period will have little direct impact on its yield. A general guideline is to keep vegetable crops weed free during the first one-third to one-half of their life cycle. Weed-free periods for vigorous, fast-growing crops like vining cucurbits, snap beans, soybeans, tomatoes, and potatoes might be the first four to six weeks after planting, whereas slower-growing crops like peppers, eggplants, carrots, and onions need eight to ten weeks or more weed free. Perennial crops like asparagus, strawberries, and brambles may require diligent weed removal throughout their establishment year.

In practice, the minimum weed-free period for a given crop varies widely with the weed species composition, weed density, soil conditions, weather, climate, and the vigor of the crop itself. Again, continual and careful observation is the best guide for determining at what point a crop becomes tolerant to the presence of later-emerging weeds. One way to evaluate your weed control practices in relation to weed free period is to keep a small plot scrupulously weed-free through harvest. Compare the weed-free vegetable yield and quality with the yield and quality realized through your regular cultivation schedule.

Vigorous crops that form a closed canopy effectively hinder the growth of most weeds emerging after the crop's minimum weed-free period. Crop shading and competition can also reduce the number of seeds these late-emerging weeds set by 90–99% compared to the same weed species growing in full sun.

Preventing Weed Propagation

No matter how well the crop is tolerating weed pressure, flowering weeds spell trouble unless they are removed before mature seeds form. A single mature plant of common lamb's-quarter or redroot pigweed every 20 row-feet might not hurt a vigorous vegetable crop, but each individual weed can shed 100,000 seeds, causing a terrible weed problem for the next several seasons.

Invasive perennial weeds, such as johnsongrass, Bermuda grass, nutsedges, Canada thistle, and bindweeds, can begin to form new rhizomes, tubers, and other vegetative propagules within several weeks after the primary shoots emerge from the soil (Fig. 6). Even 6–12 inches of top growth by invasive perennials can support propagation, and should be destroyed by hoeing, close mowing or cultivation. Removing top growth whenever these weeds reach the 3–4 leaf stage will gradually exhaust existing underground structures.

Figure 6. The young johnsongrass (left), Bermuda grass (center) and yellow nutsedge (right) in this photo have already begun to form new underground rhizomes that can propagate and spread the weeds. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Once the vegetable is past its minimum weed-free period or is too large to cultivate or flame-weed, continue scouting the field for weeds to determine whether further measures might be needed to prevent weed reproduction. Watch for weeds that are bolting, heading, or forming flower buds, and remove them before flowers open. Some weeds can set mature seed even when uprooted shortly after pollination has occurred. Keep an eye out for growth of invasive, vegetatively-reproducing perennial weeds. Tactics to prevent or minimize weed reproduction include mowing between crop rows, mowing off weed seed stalks emerging above a low crop canopy such as sweet potato (Fig. 7), tillage or mowing promptly after crop harvest, and manual removal.

Figure 7. This sweet potato crop is not directly affected by the flowering galinsoga and lady's thumb emerging through its canopy. However, the weeds will produce mature seed unless they are removed promptly. Manual pulling is feasible only at a small scale, but mowing with the mower height set just above the crop canopy can knock out the majority of the weeds’ reproductive potential. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Whereas it is not feasible to rely solely on manual weeding for a multi-acre vegetable planting, it can make good economic sense to use manual weeding as a means to catch the smaller numbers of weeds that escape even the best cultivation practices, before they form seed. Labor costs for manual hoeing or pulling of small numbers of escapes (1–10 weeds per 300 row-ft) can be as low as $10–30 per acre, and can prevent millions of weed seeds from entering the weed seed bank. Norris (1999) cites a 30,000-acre cotton farm in California that uses this strategy, and an intensive, 400-acre vegetable farm in California’s Salinas Valley that invests up to $60/ac to rogue weeds out of cover crops. These measures can pay off in reduced weed seed banks and fewer cultivations in future years.

Detecting New Invaders

When scouting your fields, keep an eye out for new weed species, especially if:

- Organic materials from off-farm sources have been applied that could carry weed seed, such as mulch hay, uncomposted manure, or compost that has not heated enough to kill weed seeds (140°F for at least a week).

- Shifts in weed flora might indicate soil conditions such as compaction, nutrient imbalances, or other soil quality problems.

- One or more particularly troublesome weeds are known to be present on neighboring farms or in nearby ecosystems.

- An outbreak of an invasive exotic plant has occurred within the region, and coordinated efforts to detect and eradicate the invader are planned or underway.

Weed Monitoring: Low and High Tech Methods

Whereas insect IPM entails regular schedules and procedures for scouting insects in crops, only a minority of farms take a similar approach to weeds. Most often, weed scouting consists of taking note of weed growth whenever the farmer enters the field to plant, fertilize, cultivate, irrigate, tend, or harvest the crop. This may be sufficient for small-scale operations growing intensively managed crops. In larger, less-intensively managed fields, weeds can get the jump on the crop unless the farmer schedules regular visits to each field to evaluate weed growth.

Weed scientists have developed sophisticated methodologies for surveying and mapping weed infestations. Weed maps are produced from data collected at discrete intervals on a regular grid. Data are analyzed with the aid of computer software to generate a map of the weed’s distribution and levels of infestation. Weed maps are often used to target weed control measures to high priority (most weedy) areas within a large field, farm, or ranch, or to track incidence of invasive exotic weeds over a wider region.

Regional efforts to eradicate or contain noxious rangeland weeds and invasive exotic plants often entail extensive, collaborative weed mapping efforts coordinated through state departments of agriculture or land grant universities. Weed scientists map out the region, identify areas whose habitat is most conducive to the target weed’s establishment, and conduct intensive weed sampling and mapping in those areas, often using remote sensing or the Global Positioning System (GPS). Often, farmers, ranchers, or the general public are invited or urged to assist by submitting a noxious weed sighting report whenever they identify the target weed on their farms or elsewhere.

Weed scientists at the North Central Soil Conservation Research Laboratory in Morris, MN have developed software called WeedCast, available for download at no charge, whereby growers of corn and other field crops in the north-central United States can estimate the emergence potential (percent of total weed seed bank likely to germinate), emergence timing, and early season weed growth for the most common weeds in these crops. Based on extensive research, the model utilizes information such as the previous year's crop, the tillage system in use, the soil type, initial soil moisture content, and daily weather (temperatures and rainfall) data to forecast density and timing of weed emergence and weed seedling height (Forcella, 1998). This information helps the farmer to anticipate cultivation needs, and to time stale seedbed, planting, and cultivation operations for more effective weed control.

Weed Monitoring: a Practical Approach

Check each field regularly and often enough to identify critical stages of crop and weed development for timely intervention, and to evaluate efficacy of weed management practices. This weed scouting can be done whenever you scout for insect pests and beneficials, or enter the field to plant, tend, irrigate, or harvest crops. Scout for weeds every few days during crop germination, emergence, and early establishment. Later on, scouting once a week is usually sufficient. Vigorous cash or cover crops with a closed canopy may require less weed scouting.

To scout weeds, walk slowly through the field, examining any vegetation that was not deliberately planted. In larger fields, walk back and forth in a zigzag pattern to view all parts of the field, noting areas of particularly high or low weed infestation. Identify weeds with the help of a good weed guide or identification key for your region. Note what weeds species are most prominent or abundant. Note how each major weed is distributed through the field. Are the weeds randomly scattered, clumped, or concentrated in one part of the field?

Dig up some weed specimens to examine the root structure. This can be important for correct identification. Are there rhizomes, tubers, heavy taproots, or other storage structures indicative of a perennial habit, or does the weed have a lighter taproot or fibrous root mass typical of annuals? Are perennial weeds forming new rhizomes or other vegetative reproduction structures?

Keep records of your weed scouting in a field notebook. Prepare a page for each field or crop planting, and take simple notes of weed observations each time the field is monitored. Over time, your notes become a timeline of changes in the weed flora over the seasons and in response to crop rotations, cover crops, cultivations, and other weed control practices. Many growers, especially those who are certified organic, already maintain separate records for each field. Weed observations can be included with these.

Scouting records can include a simple map of the field, on which you can note crops grown, areas of heavy weed pressure, concentrations of particular weed species, and changes over time. These records and maps can help fine-tune weed management and cropping strategies; prioritize areas for cultivation, cover cropping, or other weed management tactics; and identify areas with the lightest weed pressure for planting perennial or other weed-sensitive crops.

When to Scout, and What to Look For in a New Field or Farm

An important part of shopping for farmland is to look at the weeds. The presence of highly aggressive weeds, intense weed pressure, stressed and nutrient-deficient weeds, or a weed flora indicative of low or unbalanced soil fertility or pH may foretell problems that should be considered in deciding whether to buy, rent, or how much to offer.

During your first year or two on a new farm or field, study the weeds carefully throughout the season, and be sure to get correct identification of the 5–10 most common weeds.

Once the grower has purchased or rented farmland, it pays to study the weeds closely through the first season. Note what weeds emerge, grow or reproduce at different parts of the annual cropping cycle:

- Over winter

- After primary tillage and during seedbed preparation

- After crop planting

- During crop growth and maturation

- After harvest

- During cover crop emergence and establishment.

Questions to ask include:

- What are the main weed species present at different times of year?

- When does each weed species emerge, flower, and set seed?

- What fields or areas have the worst weed pressure? The least?

- Are any particularly troublesome or invasive species present?

Make the same observations again a few years later to track changes in weed flora in response to management practices.

When to Scout and What to Look For during Vegetable Production

As discussed earlier, it is most important to scout fields for:

- Weeds emerging in the seedbed before, during, or just after crop germination

- Weeds growing during an annual crop’s minimum weed free period

- Weeds coming into bloom

- Top growth of invasive perennial weeds

- New weeds not seen before in the field or on the farm

Scout fields to evaluate effects of cultural practices such as cover cropping and crop rotation:

- How has the weed flora changed in response to changing the crops being grown?

- Has overall weed pressure increased or decreased?

- How have major weed species responded to changes in timing of tillage, planting, cultivation, and harvest associated with the crop rotation?

- Do the cover crops effectively smother weeds?

- For how long after the cover crop is tilled in, mowed, or rolled down is weed growth stopped or slowed?

After cultivation, mulching, mowing, flaming, or other weed control measures, evaluate:

- Were the existing weeds effectively killed or suppressed?

- Did the crop gain a decisive competitive advantage as a result?

- How quickly do new weeds emerge?

- Are these new weeds the same or different species from those that were removed by cultivation or other intervention?

Observing and recording the results of preventive practices and control operations is a vital part of weed monitoring. Track changes in weed flora and weed pressure over several seasons to determine whether the current production and weed management systems are giving the desired results, and what changes or improvements might be needed. Note what species of weeds seem most difficult to manage or most harmful to crop production. Once the most damaging weeds in a given field or cropping system have been identified, weed control strategies can be targeted against those species.

Monitor Field-margin Ecosystems

In addition to scouting production fields, monitor and manage uncultivated field margins and alleys between crop rows. These areas can become complex ecosystems with native and introduced weeds, grasses and clovers, and a diversity of plant-eating, predatory, and parasitic insects. Such areas of natural vegetation can be valuable reservoirs for beneficial insects and wildlife—and they can also harbor weeds or other pests that can invade the field (Fig. 8). Use the following questions to determine when it is time to mow field margins or alleys:

- Are any of the field margin weed species emerging or reproducing themselves within the field itself?

- Does the field margin flora contain any particularly troublesome weeds?

- Are undesirable weed species in the margin or alley bolting or beginning to flower?

Figure 8. This field margin of chicory, red clover, aster, daisies, and grasses can provide habitat for either beneficial or pest organisms or both, help with soil conservation, and may or may not cause significant weed problems in adjacent field areas. Maximize the benefits and minimize the damage through careful observation and timely mowing of field margins like this. Figure credit: Mark Schonbeck, Virginia Association for Biological Farming.

Optimum management of uncultivated field margins and alleys may require the grower to scout weeds and insects simultaneously. Mowing these areas to limit weed seed set can have unexpected impacts on the insect communities. Timely mowing can flush beneficial insects into nearby crops and augment biological pest control, whereas untimely mowing can flush pests into the crop. In western North Carolina, insect biocontrol specialist Dr. Richard McDonald has seen tarnished plant bugs suddenly move into broccoli and render the heads unmarketable when nearby weeds were mowed shortly before harvest. Scout the crop field and the adjacent uncultivated area just before and right after a mowing operation to evaluate impacts on the entire crop–insect–weed community.

Another approach to field margin management is to plant native grasses, wildflowers, beneficial habitat plants, or combinations of these that have little or no potential to become weeds in crop fields. These plantings can displace or exclude undesirable weeds as well as protecting field margins from soil erosion.

This article is part of a series on Twelve Steps Toward Ecological Weed Management in Organic Vegetables. For more on weed monitoring and identification, see:

References and Citations

- Forcella, F. 1998. Real-time assessment of seed dormancy and seedling growth for weed management. Seed Science Research 8: 201–209. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/10.1017/S0960258500004116) (verified 17 Jan 2011).

- Norris, R. F. 1999. Ecological implications of using thresholds for weed management. p. 31–58. In D. D. Buhler (ed.) Expanding the context of weed management. Food Products Press, New York. (Available online at: http://dx.doi.org/) (verified 17 Jan 2011).