eOrganic author:

Linda Tikofsky

Source:

Adapted with permission from: Mendenhall, K. (ed.) 2009. The organic dairy handbook: a comprehensive guide for the transition and beyond. Northeast Organic Farming Asociation of New York, Inc., Cobleskill, NY. (Available online at: http://www.nofany.org/organic-farming/technical-assistance/organic-dairy, verified 18 July 2012).

External Parasites and Diseases of the Skin

Fly Management

Flies are not only a nuisance, they can also impact farm profitability through reduced production and the spread of disease. Biting flies are capable of decreasing milk production by 15% to 30%. Because organic production prohibits synthetic insecticides, organic farmers must take a multi-faceted approach to insect control. Face flies, horn flies, and stable flies are the most common types found in the Northeast (see Table 1).

| Common Name | Location on Animal | Problem Level | Remarks |

| Face Fly | Face. | More than 10 flies per face. |

|

| Horn Fly | Back and abdomen. | More than 50 flies per side. |

|

| Stable Fly | Legs. | More than 10 flies per animal. |

|

Creating a carefully thought out fly management program and instituting it early in the fly season is essential to success. No single step will control flies; instead, it requires an integrated management plan. The best management practices for fly control are listed in order of priority.

- Start control early in the season. Since one female fly can lay 100 to 400 eggs every three weeks, waiting until a problem is noticed may be too late.

- Keep pastures and barns clean, dry, and free of manure. Since flies breed in decaying organic material and manure, removing breeding sites will reduce the population of flies. If used for bedding, spread out straw as soon as possible after its removal from stalls. Improve drainage in holding areas and exercise lots. Fence wet or muddy areas out of pastures. Move round bale feeder and scrape areas around feed bunks frequently.

- Use pheromone traps and sticky tape in barns to capture adult flies.

- Release parasitic wasps. These insects feed on fly larvae and can be released regularly throughout fly season.

- Use essential oils and botanicals. These are available from various organic supply companies and can be used as one final step in fly control on your farm. Remember to check with your certifier to be sure that the product is allowed.

- Use hydrated lime or diatomaceous earth. These may be used in dust bags to dry the hair coat of cows, making it less attractive to flies.

Ringworm, Lice, and Warts

Ringworm, lice, and warts are diseases of the skin of cattle and are usually contagious. They affect cow comfort and production and are more commonly seen during the winter months when cows spend more time inside (see Table 2).

| Disease | Cause | Contributing Factor | Signs | Management and Treatment |

| Ringworm | Trichophyton verrucosum | Immature or compromised immune systems. | Circular, grayish crusts especially on eyes, muzzle, and back. | Sunlight, fresh air; trace mineral and vitamin supplementation; local treatment with tincture of iodine or tea tree oil. |

| Lice | Sucking or biting of these ectoparasites | Crowding, winter months. | Decreased production, anemia. | Reduce overcrowding; improve nutrition and access to self groomers; hydrated lime or sulfur dust bags; permitted botanical and alternative products. |

| Warts | Papillomavirus | Immature immune systems. | Warts on head, neck, and teats, injury to skin. | Time; vaccination. |

Pinkeye

Infectious bovine keratoconjunctivitis (IBK or pinkeye) is caused by the bacteria Moraxella bovis. Conditions that irritate the eye and surrounding structures (including flies, plant material and stubble, dust, and viruses) allow infection by the bacteria. Initial signs of the disease include tearing, redness, swelling, and sensitivity to light (squinting). As the disease advances, a cloudy area may appear on the surface of the eye that gradually spreads. The eye may bulge or eventually rupture. Conventional farms usually inject antibiotics into the conjunctiva of the eye. However, organic management does NOT allow this and must rely on good fly control and prevention of irritation to the eye.

Follow good grazing practices to prevent stubble from injuring eye tissues. Consider vaccinating before fly season. Make sure nutrition is adequate. For extremely irritated eyes, place an eye patch or have your veterinarian temporarily sew the third eyelid over the globe to speed healing and lessen the pain.

Alternative Therapy for Pinkeye

The following therapies may not be scientifically evaluated or appropriate for all farms. Make sure you consult the References and Citations section at the end of this article for specific instructions.

- Calendula eyewash sprayed in affected eye twice daily.

Internal Parasites of Cattle

Animals on pasture are at higher risk for infestation by internal parasites. In your organic systems plan (OSP), develop grazing management strategies to minimize potential infection and transfer among age groups on your farm.

Nematodes

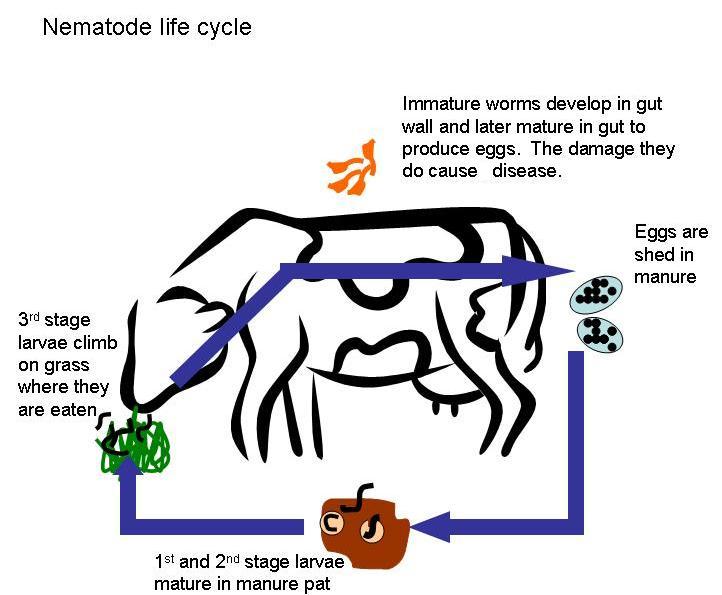

The most common intestinal worms affecting cattle in the Northeast are the brown stomach worm (Ostertagia ostertagi), the barber pole worm (Haemonchus contortus), and Cooperia spp. Larvae overwinter in cattle in the Northeast and begin to mature and produce eggs in the springtime, shedding in cattle feces. Figure 1 illustrates the nematode lifecycle.

Figure 1. Nematode lifecycle. Credit: Mendenhall, K. (ed.) 2009. The organic dairy handbook: a comprehensive guide for the transition and beyond. Northeast Organic Farming Asociation of New York, Inc., Cobleskill, NY.

Worm infestation may be clinical (visible signs) or subclinical. Clinical infections are more common in young cattle and calves. They may have diarrhea, poor weight gain, potbellies, rough and discolored hair coats, or swelling under the jaw (bottle jaw). In subclinical infestations (most common in adult cattle), diarrhea rarely occurs but the worms negatively affect milk production and body condition. Many adult cattle develop some level of immunity to intestinal parasites.

Organic farmers manage nematodes through best management practices and alternative therapies. The National Organic Program (NOP) allows synthetic dewormers (only Ffenbendazole, Ivermectin, and Moxidectin) only on an emergency basis in organic dairy cattle not designated as organic slaughter stock. Routine dewormers cannot be used. Instead, the organic system plan (OSP) must include a management plan to reduce youngstock exposure to parasites. These management steps are included in the article, "Pasture Management on Organic Dairy Farms: Pasture Pitfalls."

Alternative Therapies for Nematodes

The following therapies may not be scientifically evaluated or appropriate for all farms. Make sure you consult the References and Citations section at the end of this article for specific instructions.

- Black walnut hulls and/or wormwood.

- Garlic.

Coccidiosis

Bovine coccidiosis is caused by Eimeria spp., tiny, one-celled organisms. Most of the negative effects of coccidiosis occur in young animals (calves and heifers) and infestations are characterized by diarrhea (often with blood), weight loss, anemia, and dehydration. Death is usually due to dehydration or secondary bacterial infections.

Coccidia have a complex lifecycle. Oocysts (eggs) are shed in feces. These oocysts are quite hardy and can survive for months in moist areas, particularly where sunlight and ventilation is minimal. They are unaffected by common disinfectants. The oocysts change life stage in the environment and are then ingested by calves. Inside the calf intestine, the oocysts release sporozoites that burrow into the intestinal wall. Inside the intestinal wall, they undergo a few more life stages and eventually release more oocysts into the feces and into the environment. One ingested oocyst ultimately results in 20 million additional oocysts shed into the environment.

The severity of symptoms directly relates to the number of oocysts ingested; so, the more contaminated or less hygienic an area, the greater the risk of oocyst exposure. Overcrowding, stress, diet changes, or shipping can cause an outbreak. Follow the same best management practices used to prevent scours. The three currently NOP-approved synthetic dewormers are NOT effective for coccidiosis.

Also in This Series

This article is part of a series discussing organic dairy herd health. For more information, see the following articles.

- Organic Dairy Herd Health: General Concepts

- Alternative and Complementary Treatment and Medicines

- Youngstock Management

- Effect of Housing and Cow Comfort on Health and Disease

- Reproductive Management from Breeding through Freshening

- Udder Health and Milk Quality

- Hoof Health and Lameness

- Managing Disease in the Organic Herd

References and Citations

- Animal Welfare Information Center Bulletin [Online]. USDA National Agricultural Library. Available at: http://awic.nal.usda.gov/publications/animal-welfare-information-center-bulletin (verified 15 June 2012).

- de Bairacli Levy, J. 1991. The complete herbal handbook for farm and stable. Faber and Faber, London.

- Dettloff, P. 2004. Alternative treatments for ruminant animals. Acres U.S.A., Austin, TX

- Fraser, A. F. 1997. Farm Animal Behaviour and Welfare. CABI Publishing, New York, NY.

- Grandin, T. 2011. Outline of cow welfare critical control points for dairies [Online]. Grandin Livestock Handling Systems, Fort Collins, CO. Available at: http://www.grandin.com/cow.welfare.ccp.html (verified 15 June 2012).

- Karreman, H. 2006. Treating dairy cows naturally: Thoughts and strategies. Acres U.S.A., Austin, TX.

- Macleod, G. 2004. A veterinary materia medica and clinical repertory: With materia medica of the nosodes. Random House: UK.

- New York State Cattle Health Assurance Program Welfare/Cattle Care Module [Online]. New York State Cattle Health Assurance Program. Available at: http://www.nyschap.vet.cornell.edu/module/welfare/welfare.asp (Verified 15 June 2012).

- Sheaffer, C.Er. 2003. Homeopathy for the herd: A farmers guide to low-cost, non-toxic veterinary care for cattle. Acres U.S.A., Austin, TX.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2009. Grade "A" pasteurized milk ordinance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration. (Available online at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodSafety/Product-SpecificInformation/MilkSafety/NationalConferenceonInterstateMilkShipmentsNCIMSModelDocuments/UCM209789.pdf) (verified 15 June 2012).

- United States Department of Agriculture. 2000. National organic program: Final rule. Codified at 7 C.F.R., part 205. (Available online at: http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=1&SID=f8b2967603d1a188e3b2b1ce9afbee3c&ty=HTML&h=L&n=7y3.1.1.9.32&r=PART) (verified 7 Feb 2013).

- Verkade, T. 2001. Homeopathic handbook for dairy farming. Homepathic Farm Support Ltd., Hamilton 3240, New Zealand.

- Whole Foods Market Animal Welfare [Online]. Whole Foods Market. Available at: http://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/meat/welfare.php (verified 15 June 2012).

- Wynn, S. and B. Fougere. 2007. Veterinary herbal medicine. Mosby-Elvesier, St. Louis, MO.

Additional Resources

- Broadcast of Fly Management on Your Organic Dairy Workshop, April 19, 2012

- Fly Management in the Organic Dairy Pasture Webinar by eOrganic

- Video: Innovations on an Organic Dairy: "The Fly Barrel"