eOrganic author:

Linda Tikofsky

Source:

Adapted with permission from: Mendenhall, K. (ed.) 2009. The organic dairy handbook: a comprehensive guide for the transition and beyond. Northeast Organic Farming Asociation of New York, Inc., Cobleskill, NY. (Available online at: http://www.nofany.org/organic-farming/technical-assistance/organic-dairy, verified 18 July 2012).

Introduction

This article describes some of the common diseases that may be found within organic dairy herds. As addressed in "Organic Dairy Herd Health: General Concepts," the prevention of disease through best management practices is critical on organic dairy farms. When disease does occur, early diagnosis and intervention is essential. To be most effective, alternative treatments need to be introduced earlier and more intensively than conventional treatments.

Adult Digestive Disorders

Hardware Disease

Hardware disease (traumatic reticuloperitonitis) results from a cow swallowing a foreign object (usually metal) that lodges in the reticulum. Rumen contractions may eventually cause this object to punch a hole in the reticulum, causing inflammation and infection.

Signs of hardware disease vary in severity with the level of inflammation and infection. Cows may have objects that pose no threat residing in their stomachs for years and are only discovered at slaughter. Cows with perforations may walk with an arched back and be reluctant to eat. Other symptoms include slowed or absent rumen contractions, fever, or a positive “withers pinch test.” Pinch the backbone of the cow at the withers; cows with hardware disease will usually grunt.

If the object has penetrated and caused infection around the heart, you may hear abnormal heart sounds (like a washing machine) when you listen with a stethoscope. You may also be able to see a pulse in the jugular veins.

If severe signs are present (fever and pain), antibiotics and possibly the surgical removal of the foreign object is necessary. If antibiotics are used, the animal must be removed from organic production. This disease can be prevented (and mild cases treated) by administering magnets to cattle and ensuring that cows do not have access to foreign materials in the feed bunks or pasture.

Winter Dysentery

This digestive disorder is characterized by an acute onset of heavy, watery diarrhea caused by a coronavirus. It frequently occurs during winter housing (November through March) and likely spreads because of close contact. Once the disease starts, it usually affects all the adult animals in a herd. Although this disease is rarely fatal, it may cause a drop in milk production.

Treatment of winter dysentery is supportive: access to plenty of water so animals do not become dehydrated. Most animals will continue to eat and drink throughout the course of the disease. After a bout of winter dysentery, the herd may be immune for a few years.

Bloat

Bloat is caused by an accumulation of gas in the cow’s rumen. It usually falls within one of two categories: frothy or gassy. In mild cases, the cow belches and releases gas, but if abnormal fermentation occurs, gas may fill the rumen. The enlarged rumen puts pressure on blood vessels and restricts breathing; if the condition is not treated, death will occur.

Bloat occurs most commonly on young, lush legume pastures (particularly clovers). Moisture on the pasture (rain or dew) increases the occurrence of bloat, particularly in springtime or early summer because of the rapid fermentation of these highly digestible, early growth forages producing excess gas in the rumen. When this happens, soluble proteins are rapidly released and attacked by slime-producing bacteria. The slime forms a stable protein foam and fermentation gases buildup under this layer and the cow cannot expel them.

Bloat Prevention

• Allow only gradual access to legume pasture.

• Feed dry hay in barn before turning out onto pasture.

• Avoid turning cattle out on wet or dewy legume pasture. Allow sunlight to dry it.Treatment of bloat

• Poloxalene is allowed for the emergency treatment of bloat but is not allowed as a preventive.

• For mild bloat, remove cow from pasture and feed dry hay.

• Have the cow stand uphill so gas can more easily escape the rumen.

• Place a stick in cow’s mouth and tie it behind the ears to encourage salivation.

• For severe cases, pass a stomach tube.

• For life threatening emergencies, punch a hole in rumen with a trocar (have your veterinarian provide you with proper training and tools).Alternative Therapies for Bloat and Indigestion

The following therapies may not be scientifically evaluated or appropriate for all farms. Make sure you consult the References and Citations section at the end of this article for specific instructions.

- Indigestion: Aloe vera juice.

- Probiotics.

- Garlic.

- Bloat: vegetable oil.

Adult Respiratory Disease

Bovine respiratory disease can be a major economic drain on organic farms, causing loss of production, increased labor costs, premature culling, and death. Upper respiratory disease (URD) affects the nostrils, throat, and windpipe; pneumonia (or lower respiratory tract disease) affects the bronchial tree and lungs.

A variety of causes (see Table 1) is responsible and is often triggered by stressful environmental factors. Stressors include humidity, dust, dehydration, irritating gases from manure build-up, and nutritional deficiencies. Abrupt weather changes, cattle transport, and poorly ventilated barns may also lead to respiratory disease outbreaks.

The signs of respiratory disease indicate whether the upper or lower respiratory tract is affected and the severity of the disease. URD can be characterized by discharge from the nose and eyes, coughing, and loud sounds while breathing. Signs of pneumonia include fever, depression, lack of appetite, increased breathing rate, coughing, and death.

Best Management Practices

- Improve ventilation: Cows out on pasture are at a lower risk for respiratory disease than cows in a poorly ventilated barn. Fans improve airflow inside barns and you can retrofit many older barns with tunnel ventilation. In tunnel ventilation systems, fresh air is drawn through openings in one endwall by exhaust fans mounted in the opposite endwall.

- Vaccination: If respiratory disease is a problem on the farm, or if new cattle are introduced to the farm, consider vaccinating both the home herd and new cattle. Vaccinations should include: IBR, PI3, BVD (Types I and II), BRSV, Pasteurella, and Haemophilus somnus. Early in a herd outbreak, vaccination or boostering with an intranasal vaccine may be helpful.

- Feed quality: Dust from poor-quality hay can increase the risk of respiratory disease in a number of ways. Dust (possibly including mold spores) can act as a physical irritant on the respiratory system and may trigger allergic reactions and noninfectious pneumonia (interstitial pneumonia).

Treatment Practices

- Passive antibodies: Although not effective for viral pneumonia, these are effective for Pasteurella pneumonia.

- Vitamin B and C injections: Both of these vitamins are good anti-oxidants. You can administer both under the skin or in the vein.

- Anti-inflammatories (aspirin or flunixin): Used to reduce fever and prevent damage to lungs.

- Antibiotics: In cases where the calf does not respond to the above treatments, you must give antibiotics to prevent suffering. You must permanently remove animals treated with antibiotics from organic production.

Alternative Therapies for Adult Respiratory Disease

The following therapies may not be scientifically evaluated or appropriate for all farms. Make sure you consult the References and Citations section at the end of this article for specific instructions.

- Herbal antibiotic tinctures.

- Garlic.

- Homeopathy determined by cow's presentation and symptoms.

- Essential oils (eucalyptus).

Basic Cattle Immunology

A good organic system and a holistic health system will naturally enhance the cow's immune system. A fundamental understanding of bovine immunity will help you troubleshoot problems when disease arises and will help you make educated management decisions to enhance immunity on your farm.

Components of the Immune System that Offer a Layer of Immunity

- Skin and mucous membranes: The strength and health of the epithelium (skin of the body) is the first line of defense against disease by providing a physical barrier. Mucous membranes (nasal passages, mouth, vulva, etc.) contain skin specific antibodies (immunoglobulin A) in secretions on their surface that are first alert immunity for diseases entering via that route.

- White blood cells: These cells are produced in the bone marrow, spleen, liver, and lymph nodes and are constantly circulating in the bloodstream, patrolling for disease agents. When they encounter disease, they engulf the agent and send out warning chemicals (to recruit other white blood cells from other parts of the body.

- Lymphocytes: Lymphocytes are specialized white blood cells that produce antibodies to disease agents.

- Passive immunity: Passive immunity is achieved when is antibodies are passed from dam to calf in the colostrum. Active immunity comes through antibodies created in response to a vaccination or an illness; it is generally much stronger than passive.

Strategic Vaccination Programs

The USDA National Organic Program (NOP) allows vaccination. It is strongly recommended for open herds (e.g., when animals are bought in or sold, animals are shown in fairs, or other animals are occasionally boarded on the farm). It is always cheaper and healthier for the animal and farm budget if the farm can prevent diseases.

How Vaccinations Work

Vaccinations stimulate the cow’s immune system against specific diseases that may be present or later introduced into the herd. You should discuss vaccination with your herd veterinarian. There is no one size fits all vaccine program appropriate for every dairy. Your farm’s disease history, purchase of new animals, management, housing, breeding, cost versus benefits, and efficacy are all important considerations when evaluating whether a vaccination will benefit your farm.

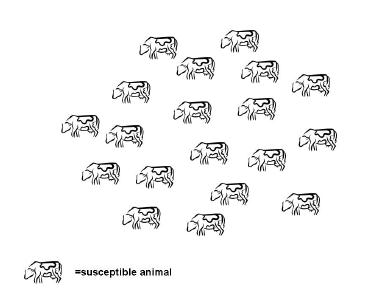

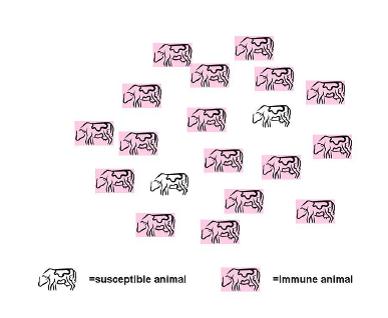

No vaccination program can protect all the animals. The goal is to build a level of herd immunity so disease cannot spread to susceptible animals. If a disease is introduced into an unvaccinated herd, 100% of the animals are susceptible. Disease may spread from the initially sick animal throughout the herd. Some may get sick and die; others will survive the infection and develop an immunity that may last weeks or a lifetime. When a disease infects vaccinated herds, the herd already has a level of immunity that slows or even halts its spread. It may therefore never reach the susceptible animals. Figure 1 illustrates an unvaccinated herd. All cows in this herd are susceptible. If a disease is brought into the herd, it can spread rapidly from cow to cow since so many animals are at risk. On the other hand, Figure 2 illustrates a vaccinated herd where 17 of the 19 animals in the herd are immune, leaving only two susceptible animals. If a disease enters this herd, it will likely encounter an immune animal and be stopped in its tracks before reaching a susceptible one.

Figure 1. Unvaccinated herd.

Figure 2. Vaccinated herd.

Types of Vaccines

There are four kinds of vaccines -- each have different benefits and drawbacks and are described in Table 1.

| Type of Vaccine | Action | Benefits | Cautions |

| Modified Live (MLV) | Multiplies in animal and stimulates white blood cells to produce antibodies. | Create a very strong immune response and usually just one vaccination is necessary. | Often not given to pregnant animals for fear of causing abortion or birth defects (IBR, BVD) |

| Killed | Inactivated virus or bacterium, so it does not reproduce in body. | Safe for pregnant animal. | Immunity is not as strong or long-lasting; requires frequent boosters; delayed development of immunity. |

| Autogenous | Bacterial or viral vaccine produced from organism or tissue of sick animal. | Used for farm-specific diseases where commercial vaccines are not available or effective. | May contain bacterial toxins, so may create allergic reaction. |

| Nosodes | Homeopathic remedy produced from diseased tissue or culture. | Used as preventive to stimulate natural immunity. | Not effective in outbreaks; not legally recognized. |

Administering Vaccines

Stress, other diseases, parasites, and poor nutrition can affect the body's ability to produce a good immune response to a vaccine and make them more susceptible to vaccine reactions. Failure to give booster vaccinations at the recommended intervals leaves animals unprotected. Poor handling of the vaccine, such as exposing it to temperature extremes, may reduce the quality and fail to stimulate a response.

Vaccinating young calves is tricky. Antibodies absorbed from colostrum often interfere with the vaccines during the first few months of life. Also, newborn calves’ immune systems are usually not mature enough to respond to vaccination.

Some people are concerned with the risks of vaccination. Some vaccines, particularly killed ones, are more likely to stimulate an allergic reaction. If a cow receives too many vaccines at one time, her immune system may be overwhelmed responding to all the vaccines and may not respond completely to one or more of them, leaving her susceptible. You should also take care using MLV vaccines. Since they are modified live viruses, animals may shed the virus for a brief time after vaccination. This may cause complications in immuno-suppressed or young animals if they are in contact with the MLV vaccinated animals. Table 2 outlines common vaccines administered on organic dairy farms.

| Disease | Conditions | Vaccination Schedule |

| Infectious Bovine Rhinotracheitis (IBR) | Respiratory disease, abortion | 4–6 months of age; prebreeding and yearly booster |

| Parainfluenza-3 (PI3) | Respiratory disease, abortion | |

| Bovine Viral Diarrhea (BVD) | Diarrhea, abortion, fever, respiratory disease | |

| Bovine Respiratory Syncytial Virus (BRSV) | Respiratory disease | |

| Bovine Respiratory Complex (Pasteurella, Mannheimia, Haemophilus) | Respiratory disease, fever | |

| Leptospirosis | Fever, abortion, blood in urine | |

| Brucellosis | Abortion, reproductive diseases, repeat breeding | Calfhood vaccination at 4–8 months (once) |

| Clostridium | Sudden death | Start at 2–6 months and booster in 2 weeks, yearly booster |

| Scours (E.coli, Corona and Rotaviruses) | Calf diarrhea | Give at 6–7 months of pregnancy |

| Pinkeye | Watery eyes, clouding, swelling | Two doses at least 30 days prior to pinkeye season |

| Coliform Mastitis | Acute mastitis, fever, depression, watery milk, death | Three doses: at dry off, two weeks later, and after freshening for herds with coliform mastitis problems |

Biosecurity

A biosecurity program is a set of management practices used to minimize the introduction to disease, spread of disease within the herd, and transport of disease off the farm. Using biosecure best management practices reduces clinical disease, improves production, and increases profitability. As always, it is easier to prevent disease than treat it.

Biosecurity Best Management Practices to Reduce Off-Farm Risks

Off-farm risks are diseases or problems that may occur from introducing animals to the farm, moving animals, or transferring biological hazards on or in objects (truck tires, boots, and water sources). The questions below address the chances that a new disease will be introduced on the farm.

When purchasing animals, you buy more than just the cow. Healthy animals may be carriers of contagious mastitis, Johne's disease, BVD, and other risks. Keeping a closed herd (where no new animals are introduced) is ideal. However, farms interested in expanding their herd may feel the need to bring in outside animals. There are steps you can take to minimize risks. Think about the following.

- What is the origin of cattle you are buying? Buying from a private, closed herd with rigorous testing is preferable to buying from an auction or cattle dealer where animals from many different farms are mixed.

- Ask for the current herd health records. Has the farm screened for contagious disease within the past year?

- Can you quarantine animals when they arrive on your farm for 3 to 4 weeks so that testing, vaccination, or treatment may be accomplished?

- Are the cattle already on the farm vaccinated? (See previous section on strategic vaccination).

There are other off-farm risks that can introduce diseases to the farm. For the following situations in open herds, taking precautionary biosecure measures lessen the risk of disease.

- Boarding and exhibiting: Boarding animals off the farm (e.g., sending heifers to a custom raiser) or exhibiting animals in fairs and shows. Protect by vaccination and quarantine for 3 to 4 weeks when they return home.

- Wildlife: Non-cattle wildlife (particularly birds and rodents) can introduce Salmonella, Cryptosporidium, Leptospirosis, rabies, and other diseases. Biodiversity is important for organic farms, but it is important to create control programs for pests and to keep feed in areas or containers where rodents and birds have minimal access.

- Manure from noncertifed herds: Use of manure from noncertified herds is allowed in organic production, but it carries some risks. Before spreading manure from the neighboring dairy on your fields, ask about the Johne’s status of the herd. High temperature composting of off-farm manure will reduce the level of infectious organisms (E. coli, Listeria, Salmonella, and Johne's bacteria) in the manure.

- Vehicles and people: Restrict access of vehicles that travel farm to farm (e.g., feed trucks) to only necessary parts of the farm and keep them out of contact with animal areas. Ask everyone to sanitize their boots on entry to your farm and wear clean coveralls. It would be good to have a boot wash station with disinfectant readily available. Request that your hoof trimmer disinfect the table and tools before it comes onto your farm.

Biosecurity Best Management Practices to Reduce Within-Farm Risks

Disease can also spread among susceptible groups on the farm. The most common scenario is milking the cows and then traveling down to the calf barn to feed the calves, wearing the same coverall and boots. Ideally, cattle should be worked in order of increasing age, with adjustments made for sick animals. Calves are the most immunologically immature animals on the farm, so make contact with this group before any others on the farm. Sick calves should be separated from healthy calves and fed and treated after the healthy group. Maternity and sick pens should be separate and sick cows should be the last group worked on the farm. Washing boots, hands, and changing coveralls between groups creates optimal biosecurity.

Best Management Practices for Specific Diseases

Johne's Disease

Johne's disease, caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium paratuberculosis subspecies avium, is a chronic wasting disease of cattle and other ruminants, characterized by weight loss and diarrhea. Infected cattle shed the bacteria in manure and may classify as light, moderate high, or super shedders depending on the number of bacteria per gram of manure. It may only take a thimbleful of contaminated manure from a heavy shedder to infect a calf.

Young calves up to a year old are most susceptible to oral infection with Johne's bacteria. Symptoms, however, rarely appear until years after the initial infection occurs. Johne's disease can also be spread in the uterus and in milk by heavily infected mothers, although this route of transmission is less common.

Best management practices are designed to prevent susceptible calves from coming in contact with adult manure. Most states have a Johne's Disease Control Program that assists farmers in designing plans to identify Johne’s disease on the farm and to work to reduce it over time. Your state veterinarian can provide additional information.

The following are the basic steps of all Johne's disease control programs.

- Establish a Johne's testing and removal program for your farm.

- This plan varies farm to farm and should be developed with your veterinarian and the state Johne’s disease coordinator.

- Small herds should fecal culture all cattle older than two years of age; larger herds may test a subset of cattle that have been statistically selected.

- Environmental screening (culture of pooled feces from concentrated cattle areas) can be performed to assess if Johne’s is present on a farm.

- Cull heavily infected animals.

- Prevent fecal to oral spread of Johne's bacteria.

- Use separate tools to scrape manure. Do not use manure contaminated tools or equipment to handle feed.

- Prevent manure contamination of the drinking water.

- Prevent run-off from adult areas to calf areas.

- Dedicate pastures for youngstock use only. Avoid leader-follower grazing schemes.

- Do not walk in the feed.

- Feed and care for calves before working with adult cattle.

- Manage calves to break the cycle of transmission.

- Know the Johne's status of the dam before calving.

- Calve cows in separate pens or expansive pasture. Pens should be dedicated to calvings and cleaned between uses.

- In herds with Johne's disease, calves should be removed from birth as soon as possible.

- Feed calves colostrum and milk from test-negative cows only.

You can access additional information on Johne's disease at: www.johnes.org and www.nyschap.vet.cornell.edu.

Bovine Viral Diarrhea (BVD)

Bovine viral diarrhea is a problem in dairy and beef cattle and other ruminants. As with Johne's disease, infected cattle may not show any outward symptoms. Although BVD was initially associated with diarrhea, we now know that the virus can cause a range of symptoms. BVD affects the cow's immune system making it more likely to contract other respiratory and intestinal diseases. Other symptoms include ulcers in the mouth and nose. If calves are infected later in gestation they may be born with birth defects.

Cattle may have acute infections or be persistently infected. Acute animals may have a fever, depression, diarrhea, or respiratory disease. BVD may cause abortions during the first trimester. Acutely infected cattle shed the virus for about two weeks and either recover completely or die. Persistently infected (PI) animals contract the disease in utero. PI animals are infected for life, constantly shedding the virus. The offspring of PI cows are also persistently infected. These infected animals may not exhibit any symptoms at all or they may be sickly and die in the first year of life. Bulls can also be infected and shed BVD in semen.

Best Management Practices for BVD

- Screen the herd for BVD in bulk milk. Your veterinarian can submit bulk milk samples to your state diagnostic laboratory for screening. Although this is an accurate test, it does not check the dry cows and calves.

- Test and remove persistently infected animals. Nasal swabs, blood (serum) samples, and ear notches can identify infected animals.

- Vaccinate to prevent additional spread.

- Screen bulls for BVD before they come to the farm or be sure your semen company uses BVD-free semen.

Bovine Leukemia Virus (BLV)

Bovine leukemia is another contagious viral disease of cattle also known as bovine leukosis or lymphosarcoma. BLV is spread among cows by blood contact. Multiple use needles and rectal sleeves, dehorning equipment, and biting flies can all spread this disease. Dams can also spread it to calves in colostrum and milk. Many cattle in the US are infected with BLV, but only a small percentage (less than 5%) develop cancer of the lymph nodes (lymphosarcoma). Finding lymphosarcoma will result in the carcass being condemned at slaughter.

Best Management Practices for BLV

- Identify and remove positive cattle by blood testing.

- Prevent the further spread in the herd.

- Use single-use needles.

- Change rectal sleeves between palpations.

- Sanitize dehorning instruments between animals or use butane or electric dehorners.

- Control flies.

Conclusion

Animals managed in organic systems have the opportunity to enjoy tremendous health and longevity, but herd health on organic farms requires a proactive, holistic approach, and not merely substituting alternative medicine for conventional synthetic treatments. As the farmer, you need to assess the animal’s condition on a daily basis so that problems are detected early. Once an abnormality is detected, you must act and treat not only the problem, but also reflect on what could be wrong in the organic management plan that is the root of the problem.

Your herd health toolbox will contain both alternative and allowed synthetic treatments. Review the contents with your veterinarian and develop standard operating procedures for common herd health problems. Work with establish organic dairy producers to educate yourself on effective alternative therapies. Remember, however, that all products may not work equally well in all situations and you may need to tailor these therapies for your farm. Finally, when alternative treatments are not effective or the severity of a disease warrants it, prohibited conventional medications MUST be used to relieve animal suffering and that animal must be removed from organic production forever.

"Treat the cow kindly, boys; remember she's a lady—and a mother."

—Theophilus Hacker, 1938

Also in This Series

This article is part of a series discussing organic dairy herd health. For more information, see the following articles.

- Organic Dairy Herd Health: General Concepts

- Alternative and Complementary Treatment and Medicines

- Youngstock Management

- Effect of Housing and Cow Comfort on Health and Disease

- Reproductive Management from Breeding through Freshening

- Udder Health and Milk Quality

- Hoof Health and Lameness

- External and Internal Pests and Parasites

References and Citations

- Animal Welfare Information Center Bulletin [Online]. USDA National Agricultural Library. Available at: http://awic.nal.usda.gov/publications/animal-welfare-information-center-bulletin (verified 15 June 2012).

- de Bairacli Levy, J. 1991. The complete herbal handbook for farm and stable. Faber and Faber, London.

- Dettloff, P. 2004. Alternative treatments for ruminant animals. Acres U.S.A., Austin, TX

- Fraser, A. F. 1997. Farm Animal Behaviour and Welfare. CABI Publishing, New York, NY.

- Grandin, T. 2011. Outline of cow welfare critical control points for dairies [Online]. Grandin Livestock Handling Systems, Fort Collins, CO. Available at: http://www.grandin.com/cow.welfare.ccp.html (verified 15 June 2012).

- Karreman, H. 2006. Treating dairy cows naturally: Thoughts and strategies. Acres U.S.A., Austin, TX.

- Macleod, G. 2004. A veterinary materia medica and clinical repertory: With materia medica of the nosodes. Random House: UK.

- New York State Cattle Health Assurance Program Welfare/Cattle Care Module [Online]. New York State Cattle Health Assurance Program. Available at: http://www.nyschap.vet.cornell.edu/module/welfare/welfare.asp (Verified 15 June 2012).

- Sheaffer, C.Er. 2003. Homeopathy for the herd: A farmers guide to low-cost, non-toxic veterinary care for cattle. Acres U.S.A., Austin, TX.

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration. 2009. Grade "A" pasteurized milk ordinance. U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, Public Health Service, Food and Drug Administration. (Available online at: http://www.fda.gov/downloads/Food/FoodSafety/Product-SpecificInformation/MilkSafety/NationalConferenceonInterstateMilkShipmentsNCIMSModelDocuments/UCM209789.pdf) (verified 15 June 2012).

- United States Department of Agriculture. 2000. National organic program: Final rule. Codified at 7 C.F.R., part 205. (Available online at: http://www.ecfr.gov/cgi-bin/retrieveECFR?gp=1&SID=f8b2967603d1a188e3b2b1ce9afbee3c&ty=HTML&h=L&n=7y3.1.1.9.32&r=PART) (verified 7 Feb 2013).

- Verkade, T. 2001. Homeopathic handbook for dairy farming. Homepathic Farm Support Ltd., Hamilton 3240, New Zealand.

- Whole Foods Market Animal Welfare [Online]. Whole Foods Market. Available at: http://www.wholefoodsmarket.com/meat/welfare.php (verified 15 June 2012).

- Wynn, S. and B. Fougere. 2007. Veterinary herbal medicine. Mosby-Elvesier, St. Louis, MO.