eOrganic author:

Rick Kersbergen, University of Maine Cooperative Extension

Introduction

In a recent University of Vermont study, organic dairy producers in that state spent nearly $1200 per cow per year on purchased feed (Parsons et al., 2009). Ninety-two percent of those purchases were for grain concentrates to increase the nutrient density of rations and improve milk production. Purchased concentrates are usually the single largest expense on both conventional and organic dairy farms.

What is Quality Forage and Why is it Important?

Organic dairy farmers must focus on providing quality forages to their livestock in order to be successful. Whether it is pasture during the grazing season or stored forages for winter months, the quality of these feeds determines what other feeds should be fed to their cows. Quality forages provide a nutritional base that maintains digestive function, improves animal health, and provides nutrients to the cow in a cost effective manner. Quality forages reduce the amount of purchased concentrates dairy producers need to buy to meet their production goals from their animals.

So what is quality forage from the cow's perspective? Most nutritionists would characterize quality forages as feeds that provide high levels of digestible nutrients, and have the potential for high intakes while maintaining rumen health. Intake potential is a great barometer of quality forages, as maximizing forage intake will result in healthy cows with good milk production.

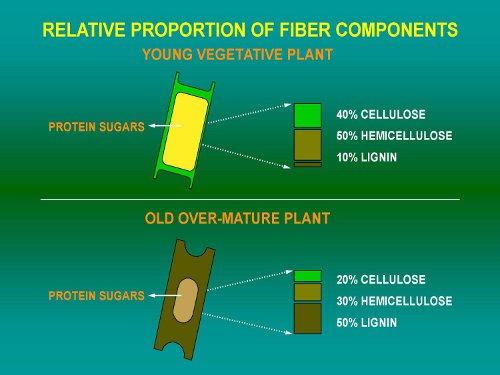

Figure 1 indicates what happens to perennial grasses and legumes as they mature from a vegetative state to a mature reproductive state. As plants mature, cell contents (which are 100% digestible) decline with an associated increase in cell walls. As the cell walls become a larger proportion of the forage, the percentage of lignin (100% indigestible) increases and the ability of the plant material to be digested by microorganisms in the cow's rumen declines. As the plant continues to mature, the concentration of protein in the plant material declines as well. Furthermore, as forages become more fibrous and less digestible, they also decrease the cow's ability to consume large amounts of feed, further reducing nutrients that are available for milk production. Maximizing intake from quality forages should be a priority for all dairy producers to maintain good production levels and body condition.

Figure 1. Relative proportion of fiber components. Figure credit: Karen Hoffman, USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Norwich, New York.

When looking at your forage analysis, you should pay close attention to the fiber levels: Acid Detergent Fiber (ADF) and Neutral Detergent Fiber (NDF). ADF helps to predict the available energy of your forage and NDF helps to predict the intake potential. Forages should be 60–100% of the cow's diet to maintain rumen health and function. A cow can usually eat 0.8% to 1% of her body weight in NDF if the quality of forage is poor, whereas she can eat up to 1.2% of her body weight in NDF if the quality of forage is high. On well-managed pastures, that percentage can go even higher (1.4% of body weight in NDF). On quality forages, total dry matter intake can reach 3.5–4% of body weight.

What Does Quality Forage Look Like on Paper?

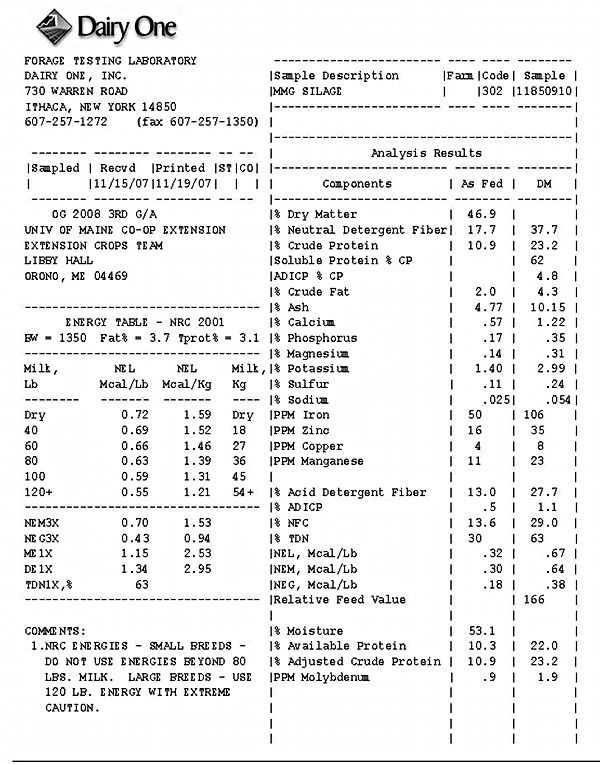

Figure 2, an example of an organic forage analysis, indicates some parameters that producers should use as goals. In this example, some indicators of quality include Crude Protein at 23.2%, NDF at 37.7 and ADF at 27.7%. NFC (Non-Fiber Carbohydrates) can be correlated with the amount of highly digestible cell contents.

Figure 2. Example of organic forage analysis conducted by Dairy One, Inc. Forage Testing Laboratory. Figure credit: Rick Kersbergen, University of Maine Cooperative Extension.

When it Comes to Protein, What Does Quality Forage Mean in Dollars?

As mentioned earlier, as plants mature the concentration of protein declines in the harvested material. Increasing forage quality from 14% to 17% crude protein (CP) through more timely harvest can have a substantial impact on a farmer's profit. For example, if organic protein were valued at $1.10 per pound, the change from 14% to 17% CP would yield about 60 pounds of protein per ton of feed. If you assume a yield of 4 tons per acre, that would represent about $240 in protein from forage per acre or $24,000 on a farm that harvests 100 acres of grass and legumes for hay or silage!

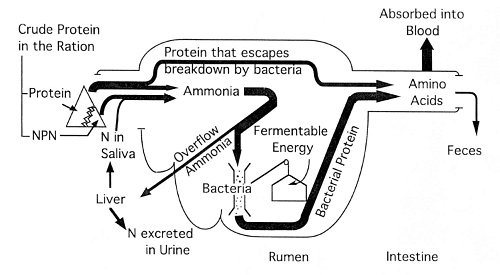

Few would argue that well-managed pasture is perhaps the best quality forage at the cheapest production cost. It can provide highly digestible nutrients—both energy and protein—harvested without fossil fuel inputs. Well-managed grass/legume pastures often have crude protein values well above the requirements necessary for dairy cows. When managing animals on pasture in an organic system, it is important to realize that what you feed to your cows in the barn will impact what and how much they eat on pasture. For every pound of forage a cow is fed in the barn, she will consume one less pound of pasture. And for every pound of grain fed in the barn, she will reduce her pasture intake by about one-half pound. Good quality vegetative pasture is extremely high in digestible protein. This protein is quickly degraded in the rumen by microorganisms that, with adequate energy, will produce high quality microbial protein that the cow can use for milk production. If there is not enough energy to match the protein, the excess gets converted to ammonia and is eventually excreted. This is an energy drain on the cow, so if you are feeding a protein concentrate while your cows are on well-managed pastures, not only are you probably wasting money, you are also reducing milk production because the cows will need to use up metabolizable energy to eliminate excess protein. Figure 3 depicts the energy and protein balance in a dairy cow.

Figure 3. Schematic summary of nitrogen utilization by the dairy cow and other ruminants. Source: Satter and Roffler, 1975.

Balancing Rations on Organic Dairy Farms

Conventional dairy farms have always fed for maximum milk production. While this makes economic sense in most situations, organic dairy producers often choose a different paradigm. With concentrate costs often 200–300% higher than conventional farms, producers need to find a level of concentrate supplementation that fits their organic system and their goals. In addition to energy and protein, dairy cows will also probably need additional sources of minerals, such as calcium and phosphorus, and vitamins to maintain their health and production. Many organic mineral and vitamin supplements are available, such as kelp.

What about Feeding No Grain Concentrate?

Most numbers will show that feeding grain is still cost effective even at high organic prices. It is important to realize that there is an ideal energy to protein ratio that needs to be met in the cow's rumen for quality fermentation products and milk production. High quality pasture that often exceeds the animal's protein requirement without any supplemental energy will result in excess nitrogen being excreted—an energy drain on the cow. Often a small amount of fermentable energy (for example molasses or finely ground corn or barley) as a supplement can make a large impact on rumen efficiency, and increase production and/or body weight gain.

Much of the genetics on dairy farms today has not been selected to perform well without a supplemental fermentable energy source. Many grass-based dairy farms are now selecting and building a genetic base that will perform better on no-grain or limited-grain diets while on pasture.

References and Citations

- Hoffman, K. 2008. Relative proportion of fiber components. In Forage quality for organic dairy production. Maximizing milk on homegrown feeds workshop. 13–19 March 2008. USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service, Norwich, NY.

- Parsons, R. L., G. Rogers, D. Kauppila, L. McCrory. 2009. Profitability of organic dairy, 2007 [Online]. NODPA Industry News, Northeast Organic Dairy Producers' Alliance. Available at http://www.NODPA.Com/in_dairy_profitability_060109.shtml (verified 20 March 2010).

- Satter, L. D., and R. E. Roffler. 1975. Nitrogen requirement and utilization in dairy cattle. Journal of Dairy Science 58: 1219–1237. (Available online at: http://jds.fass.org/cgi/content/abstract/58/8/1219) (verified 20 March 2010).