eOrganic author:

Alex Stone, Oregon State University

Introduction

Late blight is a serious disease of potato family (Solanaceous) crops worldwide, caused by the pathogen Phytophthora infestans. Late blight is favored by high humidity, dew, wet weather and moderate temperatures (50 to 80°F). When the environment is favorable, the disease can spread quickly and can defoliate fields within 3 weeks. Late blight affects foliage of both potato and tomato as well as potato tubers and tomato fruit.

Late blight is a very difficult disease to manage organically. Organic farmers should employ all strategies available to reduce late blight risk in host crops.

Before Planting

Know the pathogen

The first steps in managing any pest are 1) identifying it when you encounter it in the field, and 2) understanding its life cycle so you can exploit its weaknesses. For more information on Phythophthora infestans/late blight diagnostics and life cycle, see the Michigan State (Kirk et al., 2004) Extension bulletin referenced at the end of this article.

Late blight lesions on a potato leaf. Photo credit: Lane Selman, Oregon State University.

Destroy all sources of inoculum

In most areas of the US, the late blight pathogen is an obligate parasite, meaning that it can only survive in living plant tissue. Therefore, destruction of all living hosts of the pathogen is an important control strategy. This means destroying all cull piles and volunteer hosts (potato, tomato, eggplant, pepper), including hairy nightshade. Waste potatoes can be fed to animals, buried 2 feet deep, composted, or spread on the surface of the soil to be frozen during the winter months. Volunteer potatoes and tomatoes should be removed by cultivation.

Site selection

Choose fields with good air movement and well drained soils. Do not plant susceptible crops in fields: 1) in which host plants may volunteer/grow (volunteer seedlings of host crops or weeds/hairy nightshade); 2) next to cull piles of tomatoes or potatoes; or 3) shaded by trees or structures.

Seed selection

By law, certified organic farmers must buy certified organically-grown seed if available.

- Potato: Phytophthora infestans, the pathogen that causes late blight, is easily transmitted by diseased potato tubers. Planting potato seed that you have saved or obtained from neighbors increases late blight risk. Purchase certified seed potatoes (potato SEED certification, not organic certification) from high quality sources. Certified seed is not guaranteed to be late-blight free, but in general, certified seed should be less risky because certified seed production is monitored by seed professionals and certified growers tend to be well informed about significant potato pests affecting seed quality. Inspect your seed potatoes for late blight symptoms upon arrival, and if seed is stored before planting, inspect it again before planting as late blight can spread during storage. If late blight is suspected, have diseased tubers diagnosed by a crop consultant or plant disease diagnostician. Do not plant infected tubers as they are an excellent source of primary (initial) inoculum to start an early epidemic. On organic farms, early epidemics have a high likelihood of destroying the entire crop.

- Tomato: The late blight pathogen is NOT transmitted by tomato seed.

Resistant varieties

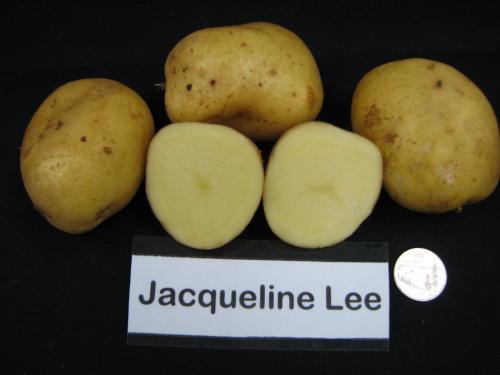

- Potato: There are a few potato cultivars available in the US that have moderate to strong foliar (and tuber) late blight resistance: Defender (russet, brown skin and white flesh; Novy et al., 2006); Jacqueline Lee (round, yellow skin and flesh; Douches et al., 2000); and Ozette (fingerling, white skin and flesh; Vales and Yilma, 2007). All three of these potato cultivars were highly rated for marketability and flavor when grown on fresh market organic farms in western Oregon and Washington (OSPUD project). US plant breeders are focusing on the development of late blight resistant potatoes; new resistant cultivars should be available in the near future.

- Tomato: There are some commercially available tomato cultivars with resistance in tomato to late blight. As described above for potatoes, US breeders are in the process of developing new disease resistant tomato cultivars.

- Recent Organic Seed Alliance trials conducted in 2006 and 2007 in Washington State indicated that the tomato cultivars Stupice and Juliet have some resistance to foliar late blight. Juliet also exhibited some resistance to early blight (Alternaria solani). Phythophthora infestans isolates were isolated from diseased tissue and identified as US-11. (Dillon et al., 2008)

- Washington State University trials in 1998 and 2000 in Mt. Vernon, Washington, indicated that Matt's Wild Cherry has some resistance to foliar and fruit late blight. Both US-8 and US-11 isolates of Phythophthora infestans were isolated from diseased tissue. (Inglis et al., 1999 and 2001)

Defender, a russet potato bred by University of Idaho, and Jacqueline Lee, a round, yellow-fleshed potato bred by Michigan State University. Defender and Jacqueline Lee were highly rated for productivity and flavor when grown on fresh market organic farms in Oregon and Washington (OSPUD). Photo credits: Lane Selman, Oregon State University.

Planting date

Manipulation of planting date to manage late blight will depend on local conditions and risk periods. In areas where the highest likelihood of late blight onset is late in the season, plant short season varieties early so foliage has died back before high risk periods begin. If risk is highest during the spring, plant later to avoid spring epidemics. If risk occurs throughout the growing season, planting timing is unlikely to reduce disease risk. However, spacing planting dates from early to late might help spread risk across plantings. Spatially separating plantings will reduce the risk of late blight spread from planting to planting.

During the Production Season

Protected culture

Late blight epidemics are much more likely to occur during periods of extended leaf wetness. Therefore, production of tomatoes in high tunnels with drip irrigation should dramatically reduce late blight risk by eliminating the contribution of rain and overhead irrigation to leaf wetness. Potatoes are not typically grown in protected culture, but if late blight is a serious problem and the crop has high value (specialty potatoes, retail market), protected culture might also have merit as a potato late blight management strategy. Make sure to ventilate greenhouses and high tunnels to minimize leaf wetness.

Field design

Plant in wide rows oriented with the prevailing winds to promote good air movement and reduce leaf wetness. Intercropping could reduce late blight risk. The BlightMOP project reported that intercropping potatoes with non-host crops (rows planted perpendicular to the prevailing winds) showed some potential to reduce disease spread in infected fields in European Union research trials (Leifert and Wilcockson 2005). In addition, intercropping rows of resistant and susceptible potato cultivars, as well as planting mixed seed of resistant and susceptible cultivars, also reduced disease severity in some trials.

Staking and pruning (tomatoes)

Stake and prune tomatoes to promote air movement and reduce leaf wetness. Do not stake and prune when wet, as diseases can be spread by people and tools.

Hilling (potatoes)

High hilling, and prevention of crack development in hills, can reduce the movement of late blight spores through the soil to tubers, thereby reducing tuber late blight risk.

Irrigation management

Manage irrigation to minimize the duration of leaf wetness. In many regions of the country, foliage becomes wet from dew during the early morning hours. If this occurs in your production area, irrigate during the early morning hours so the irrigation coincides with the leaf wetness period contributed by dew. Alternately, irrigate during the middle of the day, so the foliage goes through a drying period early in the morning and again before dark. Do not irrigate in the afternoon if the foliage cannot dry before dark; wet foliage at dark will typically remain wet all night long, resulting in a very long wetting period and increased disease risk. If applicable, use drip irrigation to minimize irrigation-applied leaf wetness.

Crop nutrition

Do not oversupply nitrogen to the crop, either through high rates of soil nitrogen mineralization and/or organic fertilizer applications. High N plants produce fewer tubers (potatoes) or fewer fruits (tomatoes) and also produce a large, lush canopy. Large, lush canopies dry slowly after wetting, increasing the risk of late blight infection. In addition, high N plant tissue is more susceptible to infection than low N plant tissue.

Weed management

Weeds in the field impede airflow, so manage weeds. Volunteer tomatoes and potatoes, and the weed hairy nightshade, are hosts to late blight, so specifically eradicate these plants in your fields.

Scouting

As an organic farmer you may wonder whether scouting is of any value, as most late blight management strategies available must be in place BEFORE late blight is observed. However, scouting is of value for several reasons: 1) You will know whether or not you have late blight in a specific field. If you DON'T have late blight in a field, you will not have to take precautions before, during and after harvest, and in subsequent years in that and neighboring fields, to minimize late blight survival and spread. 2) If first symptoms are detected immediately, the few reactive management strategies available to you could be employed, such as destruction of plants, more frequent copper applications, more strict irrigation management, or if the crop is close to harvest, immediate foliage destruction and subsequent crop harvest.

Materials

Copper products can effectively control, or slow down, late blight epidemics. Copper products have no "kick-back" activity. Therefore, they need to be applied to all plant surfaces before infection (before symptoms are observed in the field) and frequently so new foliage is protected as plants grow. In addition, they must be applied so ALL plant surfaces are covered, including the undersides of leaves where Phytophthora infestans sporulates (makes the spores that cause infections). Compost teas and other non-copper materials may have some efficacy. For more information see Organic Management of Late Blight of Potato and Totato with Copper Products.

NOTE: Before applying ANY copper product, be sure to 1) read the label to be sure that the product is labeled for the crop you intend to apply it to and the disease you intend to control, and 2) make sure that the brand name product is listed your Organic System Plan and approved by your certifier. For more information see Can I Use this Product for Disease Management on my Organic Farm?

Destruction/roguing of diseased plants

Some studies have shown that destroying the first diseased plants in a field can stop or slow disease movement throughout the rest of the field. It takes approximately three days to one week (depending on environmental conditions) from infection of a plant by the pathogen to development of symptoms. During that period, more infections are initiated on neighboring plants. Therefore, by the time the first infected plants show symptoms, many neighboring plants are infected as well. As the result, many apparently healthy plants must be destroyed in the area surrounding the first symptomatic plants in order to destroy infected, non-symptomatic plants. Michigan State University research suggests that, under Michigan conditions, all plants in a 100 ft radius from the first symptomatic plants must be destroyed (Kirk et al., 2007). A rigorous scouting program must be in place to detect the very first late blight symptoms in a field in order to make plant destruction effective. In small fields, too many plants may have to be destroyed for this to be an effective management strategy.

Another strategy is to destroy ALL foliage in a diseased field to prevent spread of the disease to other plants and tubers, or to neighboring fields. For potatoes, destruction of all foliage in the field is only recommended during later stages in tuber bulking, as tubers will cease growth when the foliage is dead.

Harvest

- Potato: Let plants die back completely before harvest. In most areas of the US, the late blight pathogen is an obligate parasite, meaning that it can only survive in living plant tissue. Therefore, killing the potato foliage also kills the pathogen living in that foliage. Dieback can be encouraged in several ways. First: don't overfertilize with nitrogen. Low N status encourages die-back, as well as minimizes N losses from the decomposing potato foliage after harvest. Second: flail, spray out (with approved herbicides - check with your certifier), or burn any living foliage. Once vines are dead, wait two weeks before harvesting the tubers to ensure that the pathogen is not longer viable in the foliage and all diseased tubers are fully decomposed; these measures should minimize disease spread. Do not harvest tubers when wet, as moisture increases the risk of spreading pathogen propagules. Harvest diseased tubers separately from healthy tubers to minimize disease spread. Late blight can spread during storage, so cull diseased tubers from diseased lots before storage. Destroy all culls.

- Tomato: Do not harvest when foliage is wet, as the pathogen sporulates during periods of leaf wetness and spores can move with people, tools and equipment from plant to plant and field to field. Cull and destroy diseased plants and fruits - do not leave them lying in the field or greenhouse.

After Harvest

- Potato: Store tubers from diseased fields separately from tubers from healthy fields. Potatoes should be stored dry and at the lowest temperature possible to suppress pathogen growth and spread. Scout all stored potatoes frequently and remove diseased tubers from storage to prevent disease spread. Destroy culls.

- Tomato: Cull diseased tomatoes and destroy the culls. Do not store tomatoes harvested from diseased fields with tomatoes from healthy fields, as disease can spread during storage.

References and Citations

- Dillon, M., J. Navazio, K. Dean, M. Rosemeyer. 2008. Public breeding for organic agriculture: Screening for horizontal resistance to late blight in tomatoes [Online]. Organic Farming Research Foundation Report. Available at: http://ofrf.org/sites/ofrf.org/files/docs/pdf/ib16.pdf (verified 18 March 2010).

- Douches, D., K. Jastrzebski, J. Coombs, W. Kirk, K. Felcher, R. Hammerschmidt, R. Chase. 2001. Jacqueline Lee: A late-blight-resistant table stock variety. American Journal of Potato Research 78 (6):413-419. (Available online at: https://www.msu.edu/~douchesd/releases/JacquelineLee_info.pdf) (verified 18 March 2010).

- Fry, W.R. 1998. Late blight of tomatoes and potatoes [Online]. Cooperative Extension of New York State Cornell University. Ithaca, NY. Available at: http://vegetablemdonline.ppath.cornell.edu/factsheets/Potato_LateBlt.htm (verified 18 March 2010).

- Inglis, D., B. Gundersen, and M. Derie. 2001. Evaluation of tomato germplasm for resistance to late blight, 2000. Biological and Cultural Tests for Control of Plant Diseases 16:PT77.

- Inglis, D., B. Gundersen, M. Derie, E. Vestey. 1999. Evaluation of tomato cultivars for resistance to late blight, 1998. Biological and Cultural Tests for Control of Plant Diseases 14:117.

- Kirk, W., P. Wharton, R. Hammerschmidt, F. Abu-el Samen and D. Douches. 2004. Late Blight [Online]. Michigan State University Extension Bulletin E-2945. East Lansing, MI. Available at: https://www.canr.msu.edu/resources/michigan_potato_diseases_late_blight_e2945(verified 18 March 2010).

- Leifert, C. and S. J. Wilcockson. 2005. Blight-MOP: Development of a systems approach for the management of late blight (caused by Phytophthora infestans) in EU organic potato production [Online]. University of Newcastle, UK. Available at:http://www.coreorganic.org/library/EU_folder/blight-mop.pdf (verified 4 April 2011).

- Novy, R., S. Love, D. Corsini, J. Pavek, J. Whitworth, A. Mosley, S. James, D. Hone, C. Shock, K. Rykbost, C. Brown, R. Thomton, R. Knowles, M. Pavek, N. Olsen, and D. Inglis. 2006. Defender: A high-yielding, processing potato cultivar with foliar and tuber resistance to late blight. American Journal of Potato Research 83 (1): 9-19.

- Plant Variety Management Institute. 2008. Defender [Online]. Available at: http://www.pvmi.org/Storage/General/Defender%20Flyer%205%2008.pdf (verified 18 March 2010).

- Rowe, R., S. Miller, and R. Riedel. Undated. Late blight of potato and tomato. Ohio State Extension Bulletin HYG-3102-95. Columbus, OH.

Additional Resources

- Powelson, M., R. Ludy, H. Partipilo, D.Inglis, B. Gunderson, M. Derie. 2002. Seedborne late blight of potato [Online]. Plant Management Network. Available at: http://www.plantmanagementnetwork.org/pub/php/management/potatolate/ (verified 18 March 2010).

- Selman, L., N. Andrews, A. Stone, and A. Mosley. 2008. What's wrong with my potato tubers [Online]? Oregon State University Extension Bulletin EM 8948-E. Corvallis, OR. Available at: http://ir.library.oregonstate.edu/xmlui/bitstream/handle/1957/20496/em8948-e.pdf (verified 18 March 2010).

- Warren, G. 2008. A potato with a past: Makah Ozette. The Slow Food USA Blog. Available at: https://www.slowfoodusa.org/blog-post/a-potato-with-a-past-the-makah-ozette (verified 18 March 2010).