eOrganic author:

Geoff Zehnder, Clemson University

Insect Sampling

Insect sampling is also sometimes referred to as scouting or monitoring. Why is sampling for pest and beneficial insects so important? Because it is of utmost importance for farmers and pest managers to understand insect activity in their crops and fields before they can make cost-effective and environmentally sound pest management decisions. Remember the underlying concept of Integrated Pest Management (IPM) is that no action is taken against a pest unless the pest is present and poses a threat to the crop. Thus, the main objectives of insect sampling (pest and beneficial) are to:

- Detect species that are present

- Determine their population density

- Determine how they are distributed in the field

Insect Sampling Techniques

There are many different insect sampling techniques and sampling equipment that can be used to detect insects in the air, on plants, and even on and beneath soil. Check the Appendix at the end of this article for references that provide a thorough overview of the various insect sampling techniques.

Row crop growers often use sweep nets to sample insects on plants like soybeans and cotton, because sweep sampling (i.e. a given number of sweeps per sampling location) is quicker and more cost effective for larger fields than inspection of individual plants. Small-scale vegetable growers more commonly sample a given number of individual plants per sampling location in the field. In this module we’ll focus on sampling methods that will provide a “relative” estimate of insect population density based on the sampling unit (i.e. numbers per leaf, per plant, etc).

Figure 1. Sweep net sampling for insects. Photo credit: Norman E. Rees, USDA Agricultural Research Service, ipmimages.org

When and How Often Should I Sample?

Optimal timing of sampling depends upon the life history and behavior patterns of the pest or beneficial insect and also on the crop and environmental conditions. Both insects and plants develop quickly under warm conditions and more slowly when it is cool. But in general it is a good idea to begin sampling as soon as the crop is transplanted into the ground or when plants emerge from the soil if direct seeded.

Sampling should be done at least once per week and preferably at least twice during warm growing conditions. More frequent sampling is usually needed if insect pest numbers are in the low-to-moderate range and on the increase. It is truly amazing how quickly insect pest populations can develop, and once-a-week sampling may not detect a surge in insect numbers until it is too late.

Sampling Procedures

There are different sampling procedures that can be used depending on the crop, size of field, etc. Farmers usually develop their own customized sampling plans once they have experience with a particular crop. Here are some guidelines for getting started.

Upon entering the field make a quick visual examination of the field. Look for any atypical areas that might affect your sampling pattern; i.e. areas with poor stands, obvious topographical variation in the field, varietal growth differences, etc. Sampling can be done in these areas but any unusual conditions that could affect insect numbers should be noted on the sampling sheet.

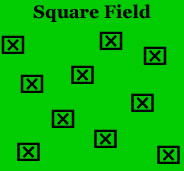

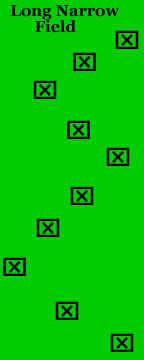

Once you have an idea of the field conditions and layout, think about an efficient sampling pattern for the field. For example, "W" or "U" shaped sampling patterns are more commonly used in a square-shaped field. In a long narrow field, a "zig-zag" or “Z” sampling pattern is usually more efficient.

In the Fig. 2 diagrams below a single sample or subset of samples would be taken at each marked location. A single sample could be a visual count of all insects on one plant. A subset of samples could be a visual count of all insects on each of 5 adjacent plants at each location. Subset samples can provide a better population estimate for insects that are not randomly distributed in the field but have an aggregated or clumped distribution.

Figure 2. Appropriate sampling patterns for square and rectangular fields. Figure Credit: Kelly Gilkerson, Clemson University Sustainable Agriculture Program

For most pests it is important to walk a few rows into the field before sampling the first plant to avoid edge effects. However, edge sampling is commonly done for pests like spider mites that commonly invade into the field from the field borders. You may wish to keep a separate data sheet for sampled plants on the field edges.

The more plants in the field that are sampled, the more reliable the sampling data. Obviously there is a trade-off between the number of plants that can be practically inspected and the level of confidence in the data that one will accept. An internet search will yield insect sampling plans for various crops, including a recommended number of plants to sample per acre.

Recordkeeping

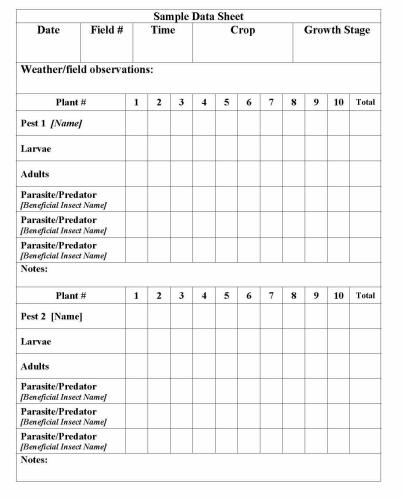

Develop a field data sheet template that you can use to record insect counts. It will probably require a few sampling periods to refine the data sheet for a particular crop, pest and beneficial insect system.

Data sheets are most commonly organized in a matrix format with sample number along one axis and labels for key pests and beneficials (by life stage) along the other axis. Thus at each sample location the actual numbers of each specific insect and stage can be entered. It is helpful to include a “total” column for each insect and stage to facilitate calculation of averages. Averages can be used as a relative measurement to determine population trends over time.

The data sheet should also include the sample date, time of day, field number or field location if sampling from separate locations, plant growth stage, and space to record other pertinent information such as atypical environmental conditions.

Figure 3. Sample field data sheet for recording insect counts. Figure Credit: Kelly Gilkerson, Clemson University

Entering sampling data into a computer spread sheet program has many advantages. In addition to simplifying data analysis, storage and retrieval, converting your data into electronic form facilitates information sharing across farms and regions. A hand held computer can also be used to record data directly from the field.

A Word about Treatment Thresholds

Back in 1959 Dr. Vern Stern, an entomologist at UC Riverside and one of the early pioneers of the integrated pest management (IPM) concept, proposed the term “Economic Injury Level” (EIL) and defined it as “the pest population at which pest control measures must be taken to prevent the pest population from rising to the economic injury level." IPM programs use the concept of an economic threshold level (ETL or ET), also known as an action threshold, which are related to the EIL.

To simplify these terms we’re talking about using sampling data to determine whether insect pest numbers have reached a pre-determined level above which economic loss will occur, and thus an insecticide application or other action is needed to prevent loss (Fig. 4).

Figure 4. In Integrated Pest Management, the Economic Injury Level (EIL) is defined as that pest population level at which the dollar cost of crop yield loss to the pest begins to exceed the dollar cost of the recommended control measures for the pest. The Economic Threshold (ET) is that level of pest population at which the pest, if left untreated, is likely to reach or exceed the EIL. Therefore, the ET is almost always lower than the EIL, and is considered the point at which the farmer should take action against the pest. Therefore, the ET is sometimes called an Action Threshold (AT). Figure credit: Ed Zaborski, University of Illinois.

Threshold levels have been painstakingly developed for a number of pest/crop systems and when available are commonly provided by state IPM Programs in their pest management guidelines for specific crops. However, not many insect pest thresholds have been developed for organic systems. One reason for this is because the focus of pest management in organic systems is on proactive and long-term preventative pest management strategies (see the Cultural Practices for Managing Insect Pests article). Thus in organic farming approved insecticides are only considered and used as a last resort.

Furthermore, organic systems are more complex than conventional farming systems. In addition to determining relationships between pest and crop life stage, damage and economic loss, development of treatment thresholds for organic systems would have to take into account additional factors that are difficult to quantify, including:

- A more complex crop ecosystem typical of organic farms

- The presence and impact of all potential natural enemy species

- Available hand labor to remove pests or wash crops

- Consumer willingness to accept some insect damage

- Lower toxicity and shorter residual activity of approved insecticides

Determining when to use an approved insecticide in organic systems

To comply with National Organic Program rules, organic farmers must have a long-term pest management plan in place that includes a number of preventative pest management tactics, including cultural practices to reduce pests and attract beneficials, use of resistant varieties, crop rotations, etc. Although approved insecticides are only to be used as a last resort, treatment is sometimes necessary to protect an organic crop from serious insect pest damage that may reduce yields and have a negative economic impact.

So how do organic farmers collect information to determine when treatment is needed? First they check with insect and crop specialists and other organic farmers to find out if treatment thresholds adaptable for organic systems in their region are available. For example, organic broccoli producers in the mountains of North Carolina use treatment thresholds for caterpillar pests developed back in the 1980s by entomologists at the University of Missouri. Dr. Richard McDonald of Symbiont Biological Pest Management has adapted and validated the thresholds for application of Bacillus thuringensis insecticides against caterpillar pests of broccoli in the NC mountain region. The thresholds are based on plant growth stage, caterpillar size, number and location on the plant.

In many cases organic farmers must develop and validate their own treatment thresholds based on available information and experience. For example, at the Clemson University Student Organic Farm, we use a treatment threshold for Colorado potato beetle on potatoes that is based on several factors including the potato beetle growth stage and the level of defoliation at various stages of potato plant growth. Field research has shown that potato plants can tolerate from 20% to 60% beetle defoliation, depending on growth stage, without any loss in yield (Table 1).

| Plant Growth Stage | Maximum Defoliation Without Yield Loss |

|---|---|

| Plant emergence to early bloom | 20% |

| Early bloom | 30% |

| Late bloom till harvest | 60% |

The potatoes are rotated and intercropped with non-potato beetle host plants, and straw mulch is also used. These cultural practices normally keep potato beetle numbers low such that defoliation thresholds are rarely exceeded. But on rare occasions when defoliation reaches threshold, approved insecticides like neem, spinosad, pyrethrin or Bacillus thuringiensis variety tenebrionis products may be used. Sprays are targeted against the small, 1st and 2nd instar larvae because small larvae are more susceptible to insecticides than larger larvae and adults.

Insect Identification

You most likely learned about the Linnean system of classifying organisms back in grade school. To review, insects are in the animal Kingdom and belong to the arthropod Phylum. Arthropods have external skeletons, jointed bodies and limbs and, in addition to insects, include crabs, lobsters, spiders, mites, centipedes and millipedes.

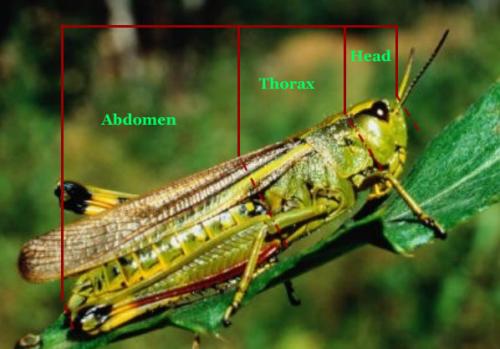

Insect arthropods are in a separate Class called Insecta distinguished from other arthropod classes by having three distinct sections: the head, thorax, and abdomen (Fig. 5). Insects can also be distinguished as having three pairs of legs attached to the thorax, and a pair of antennae on the head with some rare exceptions. Most insects have wings in the adult stage but again there are some exceptions.

Figure 5: Diagram of head, thorax and abdomen. Figure Credit: Kelly Gilkerson, Clemson University

What level of identification do I need?

At a minimum insect pests must be identified to Order to select an appropriate, approved insecticide if needed. This is because approved biological insecticides like Bacillus thuringiensis have specific activity against certain insect orders, like Lepidoptera, Coleoptera and Diptera. But identification to species is required for other biological insecticides like the insect granulosis and nuclear polyhedrosis virus products that are species specific.

But, whenever possible, key insect pests and beneficials should be identified down to the species level. Why? Because it is often the case that species within the same family and even genera will exhibit greatly different behaviors and may even have different host plants and natural enemy complexes. An identification to species will enable the gathering of all pertinent information about the species that can be used to formulate an effective management strategy.

How do I identify insects in the field?

Many different insect characteristics are used by taxonomists to identify and classify insects including wing number, wing shape and venation, structure of antennae, legs or tarsi, mouthparts, and internal structures like genitalia. You are in luck that a course on insect taxonomy is well beyond the scope of this article. However, with some practice and knowledge of available resources you will soon become an “expert” at identifying insects in your field.

Tools to aid in identification:

- Hand lens - aids in identification of tiny insects and arthropods like thrips, minute pirate bugs and mites

- Digital camera - you can use a digital camera to take and record insect images that can be sent to the local extension office for identification. Once the insect is identified the digital image can be labelled and saved for future reference

- Small vials with alcohol - useful for preserving specimens that are sent off for identification

Start with a good library

Build a reference library of insect field manuals with color pictures - for example, the Peterson Field Guide to Insects or the Simon & Schuster Guide to Insects. See also the list of reference materials and resources in the Appendix. Contact your Land Grant University extension service and/or IPM program to get their publications and fact sheets on insect pest management for the particular crops you are growing. These often contain guidelines on insect scouting and identification. Some IPM programs offer pocket guides with pictures and tips on identification and management that you can carry into the field. You can also build your own picture library with digital images you take yourself.

Get assistance if needed

Don&risqué;t panic if you are not able to confirm identification of an insect on your own; help is available. If you are an agriculture professional you probably have experience submitting insect specimens to an extension land grant university specialist for identification. In most states these services are available to the public through local extension offices, sometimes on a nominal fee basis.

Specialists are usually able to make an identification from a good digital image, but they may require an actual specimen for confirmation. If available it is best to submit an adult specimen because the adult life stage is easier to identify to species. Insect ID specialists are usually able to identify larvae to species for the more common pest and beneficial insects, but this is not always possible without an adult specimen. Always be sure to include the name of the host plant (or host insect if available for beneficials) with the specimen.

Keep records

Start a file of labelled digital images of sampled insects by year, season and crop as a reference tool to help with future identification. You can also refer to your insect scouting records from previous years to predict when key pest and beneficial insects will be present. As you learned in the “Cultural Practices for Managing Insect Pests” module, knowledge of key pests and beneficials and when they occur is key in development of preventative pest management strategies.

Additional Resources

Insect Sampling

Land Grant University IPM Programs provide online and print resources on insect sampling in various crops. An internet search by crop name and “insect pest management” is a good way to find recommendations for insect sampling in a particular crop. Here are some other useful resources:

- Ecological Methods, 3rd Edition. 2000. T.R.E. Southwood and P.A. Henderson. Blackwell Publishing, Oxford, UK.

- Entomology and Pest Management, 4th Edition. L. P. Pedigo. 2002. Prentice-Hall, Upper Saddle River, NJ.

- Radcliffe, E. B., W. D. Hutchison, and R. E. Cancelado (ed.) 2008. Radcliffe's IPM World Textbook [Online]. University of Minnesota, St. Paul, MN. Available at: http://ipmworld.umn.edu/ (verified 17 March 2010).

- Concepts in Integrated Pest Management. 2002. Edited by Norris, Kogan, Caswell-Chen & Kogan. Prentiss Hall, New York.

- Southern Region IPM Center [Online]. Available at: http://www.sripmc.org/ (verified 17 March 2010).

- Test Your Scouting Skills [Online]. University of Kentucky IPM Program. Available at: http://www.uky.edu/Ag/IPM/scoutgame/scoutlst.htm (verified 17 March 2010).

Insect Identification

Land Grant University Entomology and IPM programs provide a wealth of information on insect identification, and many provide insect identification services through an insect ID lab and/or through the statewide extension service. The following are also excellent sources of information on insect ID.

- North Carolina State Insect Notes [Online]. Available at: https://content.ces.ncsu.edu/catalog/series/166/entomology-insect-notes (verified 15 June 2020).

- University of Georgia Bugwood Network [Online]. Available at: http://www.bugwood.org/ (verified 17 March 2010).

- University of Florida “Featured Creatures” [Online]. Available at: http://entnemdept.ufl.edu/creatures/ (verified 17 March 2010).

- Insect Identification Laboratory at Virginia Tech [Online]. Available at: https://www.insectid.ento.vt.edu/ (verified 15 June 2020).

- Texas A&M Plant Pest Identification Aid [Online]. Available at: https://vegetableipm.tamu.edu/ (verified 15 June 2020).

- Clemson University Pest Identification Site [Online]. Available at: http://entweb.clemson.edu/pesticid/saftyed/pstident.htm (verified 17 March 2010).

- UC IPM Program Beneficial Insects Gallery [Online]. Available at: http://www.ipm.ucdavis.edu/PMG/NE/index.html (verified 17 March 2010).

- Online Insect Identification: West Virginia University Extension [Online]. Available at: https://extension.wvu.edu/lawn-gardening-pests/pests#id-guide (verified 15 June 2020).

- Biological Control: A Guide to Natural Enemies in North America [Online]. Cornell University. Available at: https://biocontrol.entomology.cornell.edu/index.php (verified 15 June 2020).

- The BugGuide [Online]. Available at: http://bugguide.net (verified 17 March 2010).

- Arnett & Jacques. 1981. Simon & Schuster’s guide to insects. Simon & Schuster, NY.